Joining Parties & Claims

Claims

Permissive Claim Joinder

Fed. R. Civ. P. Rule 18

(a) In General. A party asserting a claim, counterclaim, crossclaim, or third-party claim may join, as independent or alternative claims, as many claims as it has against an opposing party.

(b) Joinder of Contingent Claims. A party may join two claims even though one of them is contingent on the disposition of the other; but the court may grant relief only in accordance with the parties’ relative substantive rights. In particular, a plaintiff may state a claim for money and a claim to set aside a conveyance that is fraudulent as to that plaintiff, without first obtaining a judgment for the money.

Fed. R. Civ. P. Rule 42

(a) Consolidation. If actions before the court involve a common question of law or fact, the court may:

(1) join for hearing or trial any or all matters at issue in the actions;

(2) consolidate the actions; or

(3) issue any other orders to avoid unnecessary cost or delay.

(b) Separate Trials. For convenience, to avoid prejudice, or to expedite and economize, the court may order a separate trial of one or more separate issues, claims, crossclaims, counterclaims, or third-party claims. When ordering a separate trial, the court must preserve any federal right to a jury trial.

Burdine v. Metropolitan Direct Property and Casualty Ins. Co., No. 3:17-cv-00093-GFVT. (E.D. Ky. Nov. 1, 2018)

GREGORY F. VAN TATENHOVE, District Judge

Plaintiff Paulina Brooke Burdine originally filed this lawsuit against defendant Metropolitan Direct Property and Casualty Insurance Company (hereinafter “MetDirect”) in Franklin Circuit Court. MetDirect removed the proceedings to this Court pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1332. Ms. Burdine asserts two claims against MetDirect stemming from two separate automobile accidents. MetDirect moved to sever these claims or, in the alternative, bifurcate the proceedings. For the following reasons, MetDirect’s Motion to Sever or Bifurcate is DENIED.

I

Ms. Burdine initiated this lawsuit in the wake of two separate automobile accidents. Collision one took place in Scott County, Kentucky when Sandy Strong ran a red light and struck Ms. Burdine’s vehicle. Ms. Strong admitted fault, and her insurance policy paid Ms. Burdine to its limits. Collision two took place in Fayette County, Kentucky when Phillip Smith failed to yield the right of way to Ms. Burdine and struck her vehicle. Again, Mr. Smith admitted fault and his insurance paid Ms. Burdine to its limits. Id. At all relevant times, Ms. Burdine carried Underinsured Motorist Insurance from MetDirect.

On both occasions, the drivers carried only $25,000 in liability insurance. Ms. Burdine alleges that her medical expenses from each accident exceed the $25,000 that she received from the other drivers’ insurance policies. Ms. Burdine now wishes to collect compensation from MetDirect, her own insurance carrier, because her hospital expenses are in excess of what she received from the policies of the other drivers.

II

A

Joinder of claims is governed by Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 18, which states “a party asserting a claim, counterclaim, crossclaim, or third-party claim may join, as independent or alternative clams, as many claims as it has against an opposing party.” The scope of Rule 18(a) is well settled: “The claims which may properly be joined under Rule 18(a) include those which arise out of separate and independent transactions or occurrences, as well as those which arise out of a single transaction or occurrence.”

MetDirect argues that Ms. Burdine’s claims against it are improperly joined in a single action and should be severed. In support of its position, MetDirect cites Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 20(a)(2), which governs the joinder of parties. But this is the wrong rule. “Rule 20 deals solely with joinder of parties and becomes relevant only when there is more than one party on one or both sides of the action. It is not concerned with joinder of claims, which is governed by rule 18.”

MetDirect is correct that Ms. Burdine has asserted two separate claims involving two separate, negligent drivers. In its motion, MetDirect tries to analogize this suit to one against two separate, negligent drivers, and argues that Ms. Burdine will have to prove their negligence to recover at trial. But Ms. Burdine has not sued these drivers in negligence. Rather, she is suing MetDirect in contract, and whatever evidence of the drivers’ negligence Ms. Burdine will have to show at trial, those drivers are not defendants. There is but one defendant in this action—MetDirect—and Ms. Burdine has two claims against that defendant. As such, Ms. Burdine’s claims are properly joined under Rule 18(a). Whether or not Ms. Burdine could have sued the individual drivers for negligence in a single action is irrelevant.

B

While Ms. Burdine’s claims are properly joined against MetDirect under Rule 18, the Court may sever them if inconvenience would result “from trying two matters together which have little or nothing in common.” However, “the joinder of claims is strongly encouraged, and, concomitantly, severance should generally be granted only in ‘exceptional circumstances.’”

Rule 42 governs the bifurcation of civil trials. See Fed. R. Civ. P. 42(b). It states in relevant part, “For convenience, to avoid prejudice, or to expedite and economize, the court may order a separate trial of one or more separate issues, claims, crossclaims, counterclaims, or third-party claims.” “Bifurcation may be appropriate ‘where the evidence offered on two different issues will be wholly distinct.’” The movant has the burden of proving the appropriateness of bifurcation.

MetDirect argues that bifurcation is necessary to avoid confusing the jury. Specifically, MetDirect is concerned that “the commingling of Plaintiff’s claimed damages will .. . render it difficult, if not impossible, for the jury to accurately determine the amount of damages attributable to each incident,” which would prejudice MetDirect. But this is a problem that cannot be avoided even with bifurcation. Ms. Burdine’s collisions occurred approximately ten months apart. Ms. Burdine was still rehabilitating injuries from collision one when she was involved in collision two. At the very least, a jury assessing damages resulting from collision two will be forced to consider collision one to try and distinguish what harm is attributable solely to the second collision.

In fact, the greater risk of prejudice lies with Ms. Burdine should the Court sever these claims. To do so would force Ms. Burdine to participate in two lawsuits, greatly increasing her costs particularly with respect to medical expert testimony to her injuries. Likewise, the Court would be burdened both by the time and expense of separate proceedings in this instance. Further, as counsel for Ms. Burdine aptly puts in the Response to Defendant’s Motion to Sever:

If two trials are held, then at each trial Defendant could attempt to blame plaintiff’s injuries on the other collision. If such tactic were successful, there is the possibility that each jury could decided to attribute all of Plaintiff’s injures to the other collision and award Plaintiff nothing when in fact all of Plaintiff’s injuries are attributable to the two collisions.

Finally, the evidence offered on these two claims would not be “wholly inconsistent” such that bifurcation is necessary. The insurance companies of the other drivers, Ms. Strong and Mr. Smith, have already paid Ms. Burdine to the limit of their policies. The larger issue at trial, then, will not be their negligence, but whether the damages Ms. Burdine suffered exceed the $25,000.00 offered under the other drivers’ respective policies. Therefore, no reason exists to bifurcate these issues at trial.

III

In sum, Ms. Burdine has properly joined her claims, which sound in contract, against single defendant MetDirect. This issue is controlled by Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 18, and Rule 20 has no applicability here. Further, MetDirect will not be prejudiced by trying these claims together. On the contrary, the risk of prejudice to Ms. Burdine is high should her claims be severed, and severance would not convenience, expedite or economize the proceedings. See Fed. R. Civ. P. 42(b).

Counterclaims

Fed. R. Civ. P. Rule 13

(a) Compulsory Counterclaim.

(1) In General. A pleading must state as a counterclaim any claim that—at the time of its service—the pleader has against an opposing party if the claim:

(A) arises out of the transaction or occurrence that is the subject matter of the opposing party’s claim; and

(B) does not require adding another party over whom the court cannot acquire jurisdiction.

(2) Exceptions. The pleader need not state the claim if:

(A) when the action was commenced, the claim was the subject of another pending action; or

(B) the opposing party sued on its claim by attachment or other process that did not establish personal jurisdiction over the pleader on that claim, and the pleader does not assert any counterclaim under this rule.

(b) Permissive Counterclaim. A pleading may state as a counterclaim against an opposing party any claim that is not compulsory.

(h) Joining Additional Parties. Rules 19 and 20 govern the addition of a person as a party to a counterclaim or crossclaim.

Jones v. Ford Motor Credit, 358 F.3d 205 (2d Cir. 2004)

NEWMAN, Circuit Judge

This appeal concerns the availability of subject matter jurisdiction for permissive counterclaims. It also demonstrates the normal utility of early decision of a motion for class certification. Defendant-Appellant Ford Motor Credit Company (“Ford Credit”) appeals from the June 14, 2002, judgment of the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York (Lawrence M. McKenna, District Judge) dismissing for lack of jurisdiction its permissive counterclaims against three of the four Plaintiffs-Appellees and its conditional counterclaims against members of the putative class that the Plaintiffs-Appellees seek to certify. We conclude that supplemental jurisdiction authorized by 28 U.S.C. § 1367 may be available for the permissive counterclaims, but that the District Court’s discretion under subsection 1367(c) should not be exercised in this case until a ruling on the Plaintiffs’ motion for class certification. We therefore vacate and remand.

Background

Plaintiffs-Appellees Joyce Jones, Martha L. Edwards, Lou Cooper, and Vincent E. Jackson (“Plaintiffs”), individually and as class representatives, sued Ford Credit alleging racial discrimination under the Equal Credit Opportunity Act (“ECOA”), 15 U.S.C. § 1691 et seq. (2003). They had purchased Ford vehicles under Ford Credit’s financing plan. They alleged that the financing plan discriminated against African-Americans. Although the financing rate was primarily based on objective criteria, Ford Credit permitted its dealers to mark up the rate, using subjective criteria to assess non-risk charges. The Plaintiffs alleged that the mark-up policy penalized African-American customers with higher rates than those imposed on similarly situated Caucasian customers.

In its Answer, Ford Credit denied the charges of racial discrimination and also asserted state-law counterclaims against Jones, Edwards, and Cooper for the amounts of their unpaid car loans. Ford Credit alleged that Jones was in default on her obligations under her contract for the purchase of a 1995 Ford Windstar, and that Edwards and Cooper were in default on payments for their joint purchase of a 1995 Mercury Cougar. Additionally, in the event that a class was certified, Ford Credit asserted conditional counterclaims against any member of that class who was in default on a car loan from Ford Credit. The Plaintiffs moved to dismiss Ford Credit’s counterclaims for lack of subject matter jurisdiction, Fed.R.Civ.P. 12(b)(1), lack of personal jurisdiction, Fed.R.Civ.P. 12(b)(2), improper venue, Fed.R.Civ.P. 12(b)(3), and failure to state a claim upon which relief could be granted, Fed.R.Civ.P. 12(b)(6).

The District Court granted the Plaintiffs’ motion and dismissed Ford Credit’s counterclaims, summarizing its reasons for doing so as follows: “Defendant’s counterclaims do not meet the standard for compulsory counterclaims[, and] pursuant to § 1367(c)(4), there are compelling reasons to decline to exercise jurisdiction over the counterclaims.”

In reaching these conclusions, Judge McKenna acknowledged some uncertainty. After determining that the counterclaims were permissive, he expressed doubt as to the jurisdictional consequence of that determination. On the one hand, he believed, as the Plaintiffs maintain, that permissive counterclaims must be dismissed if they lack an independent basis of federal jurisdiction. On the other hand, he acknowledged that “there was some authority to suggest that the court should determine, based on the particular circumstances of the case, whether it had authority to exercise supplemental jurisdiction under § 1367(a)” over a counterclaim, regardless of whether it was compulsory or permissive.

To resolve his uncertainty, Judge McKenna initially ruled that the counterclaims, being permissive, “must be dismissed for lack of an independent basis of federal jurisdiction.” He then ruled that, if he was wrong and if supplemental jurisdiction under section 1367 was available, he would still dismiss the counterclaims in the exercise of the discretion subsection 1367(c) gives district courts.

On March 27, 2003, the District Court entered judgment pursuant to Fed.R.Civ.P. 54(b) in favor of the Plaintiffs, dismissing Ford Credit’s counterclaims without prejudice. Ford Credit appeals from this decision.

Discussion

I. Are Ford Credit’s Counterclaims Permissive?

Fed.R.Civ.P. 13(a) defines a compulsory counterclaim as

any claim which at the time of serving the pleading the pleader has against any opposing party, if it arises out of the transaction or occurrence that is the subject matter of the opposing party’s claim and does not require for its adjudication the presence of third parties of whom the court cannot obtain jurisdiction.

Such counterclaims are compulsory in the sense that if they are not raised, they are forfeited. Fed.R.Civ.P. 13(b) defines a permissive counterclaim as “any claim against an opposing party not arising out of the transaction or occurrence that is the subject matter of the opposing party’s claim.”

Whether a counterclaim is compulsory or permissive turns on whether the counterclaim “arises out of the transaction or occurrence that is the subject matter of the opposing party’s claim,” and this Circuit has long considered this standard met when there is a “logical relationship” between the counterclaim and the main claim.

Although the “logical relationship” test does not require “an absolute identity of factual backgrounds,” the “‘essential facts of the claims [must be] so logically connected that considerations of judicial economy and fairness dictate that all the issues be resolved in one lawsuit.’”

We agree with the District Court that the debt collection counterclaims were permissive rather than compulsory. The Plaintiffs’ ECOA claim centers on Ford Credit’s mark-up policy, based on subjective factors, which allegedly resulted in higher finance charges on their purchase contracts than on those of similarly situated White customers. Ford Credit’s debt collection counterclaims are related to those purchase contracts, but not to any particular clause or rate. Rather, the debt collection counterclaims concern the individual Plaintiffs’ non-payment after the contract price was set. Thus, the relationship between the counterclaims and the ECOA claim is “logical” only in the sense that the sale, allegedly on discriminatory credit terms, was the “but for” cause of the non-payment. That is not the sort of relationship contemplated by our case law on compulsory counterclaims. The essential facts for proving the counterclaims and the ECOA claim are not so closely related that resolving both sets of issues in one lawsuit would yield judicial efficiency. Indeed, Ford Credit does not even challenge the ruling that its counterclaims are permissive.

Ginwright v. Exeter Finance, No. TDC-16-0565 (D. Md. 2016)

CHUANG, District Judge

On February 26, 2016, Plaintiff Billy Ginwright filed this action against Defendant Exeter Finance Corporation (“Exeter”) for violations of the Telephone Consumer Protection Act (“TCPA”), 47 U.S.C. § 227 (2012), and the Maryland Telephone Consumer Protection Act (“MTCPA”), Md. Code Ann., Com. Law §§ 14-3201 to -3202 (West 2013). On May 11, 2016, Exeter filed its Amended Answer and Counterclaim, alleging that Ginwright breached the contract that led Exeter to seek to collect a debt by telephone. Pending before the Court is Ginwright’s Motion to Dismiss Exeter’s Counterclaim. For the following reasons, the Motion is granted.

Background

In May 2013, Ginwright entered into a contract with BW Auto Outlet of Hanover, Maryland to finance the purchase of a vehicle. Within the contract, BW Auto Outlet assigned all of its rights under the contract to Exeter. In his Complaint, Ginwright alleges that in seeking to collect a debt under the contract, Exeter called Ginwright’s cellular phone “hundreds of times” by means of an automatic dialing system. Compl. ¶¶ 22-23. Ginwright maintains that Exeter made the calls for non-emergency purposes and without his prior express consent. He also asserts that he repeatedly told Exeter to cease calling him, to no avail. Rather, Exeter representatives told him that they would not stop calling his cellular phone, and that the calls would continue through the automatic dialing system. As a result, with rare exceptions, Ginwright received three to seven calls from Exeter every day between December 4 and December 17, 2014; March 5 and April 29, 2015; and May 10 and June 5, 2015.

In its Counterclaim, Exeter alleges that Ginwright breached the original contract when he failed to make car payments, requiring Exeter to repossess the vehicle. Exeter contends that, following the sale of the vehicle and the application of the sale proceeds to the full amount owed, Ginwright owed a remainder of $23,782.17 under the contract as of May 3, 2016.

Discussion

Ginwright is seeking dismissal of the counterclaim pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b)(1) for lack of subject matter jurisdiction. Ginwright asserts that Exeter has failed to assert any independent basis for jurisdiction over the counterclaim and that this Court may not exercise supplemental jurisdiction over the counterclaim because it is a permissive counterclaim. Exeter counters that, since the enactment of 28 U.S.C. § 1367, a court, may exercise supplemental jurisdiction over a permissive counterclaim, and that, in any event, its counterclaim is compulsory.

III. Permissive Counterclaim

In assessing whether a counterclaim is compulsory or permissive, courts consider four inquiries:

(1) Are the issues of fact and law raised in the claim and counterclaim largely the same?

(2) Would res judicata bar a subsequent suit on the party’s counterclaim, absent, the compulsory counterclaim rule?

(3) Will substantially the same evidence support or refute the claim as well as the counterclaim? and

(4) Is there any logical relationship between the claim and counterclaim?

These inquiries are more akin to a set of guidelines than a rigid test, such that a “court need not answer all these questions in the affirmative for the counterclaim to be compulsory.”

Applying the four inquiries here, the Court concludes that Exeter’s counterclaim is permissive. First, the issues of fact and law raised in the TCPA claim and breach of contract counterclaim are largely dissimilar. The TCPA bars “any call (other than a call made for emergency purposes or made with the prior express consent of the called party) using any automatic telephone dialing system or an artificial or prerecorded voice” to any telephone number assigned to a cellular telephone service. 47 U.S.C. § 227(b)(1)(A)(iii). Thus, to prevail on this claim, Ginwright must establish that Exeter made calls to the plaintiffs cellular phone, by means of an automatic dialing system, without Ginwright’s express consent or an emergency purpose. There is no requirement to show any underlying contractual dispute or debt that led to such phone calls. Meanwhile, the breach of contract counterclaim requires proof of an agreement between the parties and a failure by Ginwright to honor the terms of that agreement to make timely car payments. According to Ginwright, his defense may be based on the assertion that Exeter did not comply with the statutorily required repossession and resale procedures contained in the Creditor Grantor Closed End Credit (“CLEC”) provisions of the Maryland Commercial Law Article, which must be satisfied in order for a lender to collect a deficiency judgment for an unpaid car loan. There is no requirement to show any use or lack of use of telephone calls to the borrower. Thus, there is little overlap between the two sets of legal and factual issues.

Second, because the legal and factual issues are different, the evidence would not be “substantially the same.” While the alleged contract underlying the counterclaim might be admissible on the TCPA claim to the extent that it is relevant to establishing prior express consent for phone calls or the lack thereof, the evidence on the TCPA claim will primarily consist of records and testimony about the number of calls received and the use of the automatic dialing system, which would be of no relevance to the breach of contract counterclaim. Likewise, Exeter’s counterclaim, which contains no allegations relating to phone calls or an automatic dialing system, will rely primarily on evidence that does not pertain to the TCPA claim, such as proof of Ginwright’s failure to make car payments and evidence that Exeter did or did not repossess the car and resell it in accordance with Maryland’s CLEC requirements.

Third, res judicata would not bar a subsequent suit on the breach of contract counterclaim. “The preclusive effect of a federal-court judgment is determined by federal common law.” An action is precluded when:

1) the prior judgment was final and on the merits, and rendered by a court of competent jurisdiction in accordance with the requirements of due process; 2) the parties are identical, or in privity, in the two actions; and, 3) the claim in the second matter is based upon the same cause of action involved in the earlier proceeding.

Claims “based upon the same cause of action” are those which “arise out of the same transaction or series of transactions, or the same core of operative facts.” As discussed above, Exeter’s counterclaim, which is associated with the sales agreement for a vehicle, derives from a different core set of facts than Ginwright’s TCPA claim, which is based on numerous phone calls placed to his cellular phone from December 2014 to July 2015. Thus, res judicata would not bar a subsequent breach of contract claim by Exeter.

Fourth, any logical relationship between the TCPA claim and the breach of contract counterclaim is a loose one. Although the TCPA claim would likely not have arisen in the absence of the original contract at issue on the counterclaim, there is little or no connection between a claim concerning the misuse of an automatic dialing system and a counterclaim alleging the failure to pay back a loan.

Considering all of the factors, the Court concludes that Exeter’s counterclaim is permissive. Although the Fourth Circuit has not addressed this precise issue, it has held that where a plaintiff alleged a violation of the disclosure requirements of the Truth-in-Lending Act (“TILA”), 15 U.S.C. §§ 1601-1667(f) (2012), a counterclaim seeking payment of the undeflying debt was permissive. In Whigham, the court concluded that the counterclaim raised “significantly different” issues of law and fact than those presented by the TILA claim and that evidence on the two claims differed because only the counterclaim depended on verification of the debt and proof of default. It also concluded that the claims were “not logically related” because although the federal claim involved the same loan, it did not “arise from the obligations created by the contractual transaction.” These same conclusions apply here, where Ginwright’s TCPA claim involves different issues of fact and law, relies on different evidence, and is no more logically related to the counterclaim than the TILA claim in Whigham was to its counterclaim.

The Court’s conclusion is consistent with those of several district courts that have held that, in the case of a TCPA claim, a counterclaim alleging a failure to pay the debt that was the subject of the telephone calls was permissive.

Exeter’s citation to a single district court case reaching the contrary conclusion, Horton v. Calvary Portfolio Servs., (S.D. Cal. 2014), is unpersuasive. In Horton, the court applied the “logical relationship” test, followed by the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit in determining whether a counterclaim is compulsory or permissive, which differs from the Fourth Circuit’s four-part inquiry. Moreover, other courts applying a logical relationship test have concluded that a breach of contract counterclaim to a TCPA claim is permissive.

Pace v. Timmermann’s Ranch, 795 F.3d 748 (7th Cir. 2015)

RIPPLE, Circuit Judge

In 2011, Timmermann’s Ranch and Saddle Shop (“Timmermann’s”) brought an action against its former employee, Jeanne Pace, for conversion, breach of fiduciary duty, fraud, and unjust enrichment. It alleged that Ms. Pace had stolen merchandise and money from the company. Ms. Pace filed her answer and a counterclaim in early 2011.

In 2013, Ms. Pace and Dan Pace, her husband, filed a separate action against Timmermann’s and four of its employees, Dale Timmermann, Carol Timmermann, Dawn Manley, and Tammy Rigsby (collectively “the individual defendants”). They alleged that these defendants had conspired to facilitate Ms. Pace’s false arrest. Ms. Pace alleged that, as a result of their actions, she had suffered severe and extreme emotional distress. Mr. Pace claimed a loss of consortium.

Ms. Pace filed a motion to consolidate these two actions. The court granted the motion with respect to discovery, but denied the motion with respect to trial and instructed Ms. Pace that she should request consolidation for trial after the close of discovery. In the midst of discovery, however, the district court dismissed Ms. Pace’s 2013 action after concluding that her claims were actually compulsory counterclaims that should have been filed with her answer to the company’s 2011 complaint. Ms. Pace appeals the dismissal of her 2013 action and the court’s denial of her motion to consolidate.

We hold that Ms. Pace’s claims against parties other than Timmermann’s were not compulsory counterclaims because Federal Rules of Civil Procedure 13 and 20, in combination, do not compel a litigant to join additional parties to bring what would otherwise be a compulsory counterclaim. We also hold that because Ms. Pace’s claim for abuse of process against Timmermann’s arose prior to the filing of her counterclaim, it was a mandatory counterclaim. We therefore affirm in part and reverse in part the judgment of the district court and remand the case for further proceedings.

I. Background

A.

The issues in this case present a somewhat complex procedural situation. For ease of reading, we first will set forth the substantive allegations of each party. Then, we will set forth the procedural history of this litigation in the district court.

1.

Timmermann’s boards, buys, and sells horses, as well as operates both a ranch and a “saddle shop,” in which it sells merchandise for owners and riders of horses. When this dispute arose, Carol and Dale Timmermann managed Timmermann’s. Dawn Manley and Tammy Rigsby were employees of Timmermann’s.

In its 2011 complaint, Timmermann’s alleged that, while employed as a bookkeeper at Timmermann’s, Ms. Pace had embezzled funds and stolen merchandise. According to the complaint, beginning at an unknown time, Ms. Pace regularly began removing merchandise from Timmermann’s without paying; she would then sell those articles on eBay for her personal benefit. Timmermann’s further alleged that it discovered that Ms. Pace was selling items on eBay through a private sting operation.

According to the complaint, in February 2011, a Timmermann’s employee discovered some of the company’s merchandise in Ms. Pace’s car. At this point, Timmermann’s fired Ms. Pace. Thereafter, during a review of its records, including the checking account maintained by Ms. Pace, Timmermann’s discovered that a check that Ms. Pace had represented as being payable to a hay vendor actually had been made payable to cash. Timmermann’s also discovered that, on at least eight occasions, Ms. Pace had utilized the company’s business credit card to make personal purchases.

2.

In her 2013 complaint, Ms. Pace alleged that her conduct while working at Timmermann’s was consistent with its usual course of business. She stated that Timmermann’s had a practice of allowing employees to use cash to purchase merchandise at cost or, alternatively, by deducting the merchandise’s value from the employee’s pay. She maintains that she had purchased the company’s merchandise under that established practice. She also alleged that Carol Timmermann, her supervisor, knew that she had sold the company’s merchandise at flea markets and never had objected.

Ms. Pace also maintained that she was instructed to write corporate checks out to cash and to note the payee in the check records. Pursuant to those instructions, Ms. Pace had written checks to cash and recorded the payee and purpose of the check in the check records. Ms. Pace further alleged that Carol Timmermann had instructed her to use Carol’s credit card, which was used as the corporate credit card, for personal purchases and to reimburse Carol, and not Timmermann’s, for those purchases.

According to Ms. Pace’s complaint, on February 14, 2011, Dale Timmermann called the Lake County, Illinois, Sheriff’s Office and accused Ms. Pace of stealing over $100,000 in merchandise from Timmermann’s. On February 14 and 15, Dale Timmermann took affirmative steps to convince the Sheriff’s Office to arrest Ms. Pace by stating that Ms. Pace had stolen approximately $100,000 in merchandise and that Ms. Pace had been changing inventory on the computer. Ms. Pace was taken into custody by the Lake County Sheriff’s Office on February 15, 2011, and released on February 16.

Following her release from custody, the individual defendants continued to provide the Sherriff’s Office with information about Ms. Pace’s allegedly unlawful conduct. On March 13, 2012, the State’s Attorney brought charges against Ms. Pace premised on the information provided by the company’s employees. Ms. Pace was charged with theft, forgery, and unlawful use of a credit card.

B.

We turn now to the procedural history of this litigation in the district court, a history that produced the situation before us today.

On March 3, 2011, Timmermann’s filed its civil complaint against Ms. Pace, alleging conversion, breach of fiduciary duty, fraud, and unjust enrichment. It sought to recover the value of the merchandise and money that Ms. Pace allegedly had stolen. Ms. Pace filed her answer and counterclaims on April 5, 2011.

On February 1, 2013, Ms. Pace and Mr. Pace (collectively “the Paces”) filed a complaint against Timmermann’s and the individual defendants, alleging that they had conspired to facilitate Ms. Pace’s false arrest. Ms. Pace alleged that she had suffered severe and extreme emotional distress; Mr. Pace claimed a loss of consortium. Specifically, the Paces’ complaint included seven counts: “false arrest/false imprisonment/in concert liability” (Count I); “abuse of process” (Count II); “intentional infliction of emotional distress” (Count III); “conspiracy to commit abuse of process and intentional infliction of emotional distress” (Count IV); “in concert activity” (Count V); “aiding and abetting abuse of process and intentional infliction of emotional distress” (Count VI); and “loss of consortium” (Count VII). Only four counts, Counts I-III and Count VII, listed Timmermann’s as a defendant. The remaining counts were directed at Dale and Carol Timmermann or the other individual defendants.

On March 15, 2013, Ms. Pace filed a motion to consolidate the two cases. On April 2, 2013, the district court consolidated the cases for the purpose of discovery and pretrial practice. The court denied without prejudice the motion to consolidate the cases for trial; it stated that it would rule on a motion to consolidate for trial after discovery.

On May 2, 2013, Timmermann’s and the individual defendants moved to dismiss Ms. Pace’s action under Federal Rules of Civil Procedure 12(b)(6) and 13(a). They contended that her allegations should have been filed as compulsory counterclaims in the 2011 action. Thereafter, Ms. Pace moved to amend her 2011 counterclaim and to consolidate the cases for trial. The district court set a briefing schedule for the company’s motion to dismiss and held Ms. Pace’s motion to consolidate in abeyance.

In December 2013, the district court granted the company’s motion to dismiss. The court concluded that Ms. Pace’s separate claims were barred because they were compulsory counterclaims that should have been brought in the 2011 action because the claims arose out of the same transaction or occurrence. Noting that her 2013 complaint had indicated that the fear of being indicted caused her emotional distress, the court held that Ms. Pace’s claims were in existence when the 2011 action was filed; it therefore rejected Ms. Pace’s argument that her abuse-of-process claim was not in existence until she was charged. In the district court’s view, the absence of Mr. Pace and the individual defendants from the 2011 action did not preclude the court’s conclusion that Ms. Pace’s claims were compulsory counterclaims because Mr. Pace and the individual defendants could have been joined in the 2011 action under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 20.

II. Discussion

The Paces now appeal the dismissal of the 2013 action. They concede that Ms. Pace’s false arrest and emotional distress claims against Timmermann’s were compulsory counterclaims and therefore properly dismissed. They contend, however, that Ms. Pace’s claims against the individual defendants and Mr. Pace’s claims for loss of consortium were not compulsory counterclaims. They also submit that Ms. Pace’s abuse of process claim against Timmermann’s did not “exist” when the 2011 action was filed and therefore could not have been a compulsory counterclaim.

A.

Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 13 governs compulsory counterclaims. Rule 13(a)(1) provides:

In General. A pleading must state as a counterclaim any claim that—at the time of its service—the pleader has against an opposing party if the claim:

(A) arises out of the transaction or occurrence that is the subject matter of the opposing party’s claim; and

(B) does not require adding another party over whom the court cannot acquire jurisdiction.

The text of this subsection limits the definition of compulsory counterclaim to those claims that the pleader has against an opposing party; it does not provide for the joinder of parties. Instead, in a later subsection, it expressly incorporates the standards set out for the required joinder of parties under Rule 19 and the permissive joinder of parties under Rule 20. Specifically, subsection 13(h) provides: “Rules 19 and 20 govern the addition of a person as a party to a counterclaim or crossclaim.”

Rule 19 requires that a party be joined if, “in that person’s absence, the court cannot accord complete relief among existing parties,” or if proceeding in the party’s absence may “impair or impede the person’s ability to protect his interest” or “leave an existing party subject to a substantial risk of incurring double, multiple, or otherwise inconsistent obligations.” Fed.R.Civ.P. 19(a)(1). In contrast, Rule 20 allows for parties to be joined if “any right to relief is asserted against them jointly, severally, or in the alternative with respect to or arising out of the same transaction, occurrence, or series of transactions or occurrences; and any question of law or fact common to all defendants will arise in the action.” Fed.R.Civ.P. 20(a)(2).

The district court did not hold, and Timmermann’s does not contend, that the individual defendants named in Ms. Pace’s complaint were opposing parties under Rule 13(a) in the 2011 action. Nor does the company’s claim that the individual defendants were required parties under Rule 19. Instead, Timmermann’s submits that, because the district court could have acquired jurisdiction over the individual defendants and could have joined them under Rule 20, it was appropriate to treat Ms. Pace’s claims as compulsory counterclaims. In essence, Timmermann’s combines the permissive joinder rule under Rule 20 with the compulsory counterclaim requirement in Rule 13 to create a rule for compulsory joinder.

The text of the rules, however, do not permit such an arrangement. Timmermann’s relies on the text of Rule 13(a)(1)(B), which provides that a claim is not a compulsory counterclaim if it “requires adding another party over whom the court cannot acquire jurisdiction.” From this statement, Timmermann’s devises that, because the district court could have exercised jurisdiction over the individual defendants, the claims against them must be brought as compulsory counterclaims. Rule 13, however, does not require the joinder of parties. Its scope is limited to the filing of counterclaims. Although Rule 13(a)(1)(B), like Rule 19, encourages that all claims be resolved in one action with all the interested parties before the court, Rule 13 fulfills this objective by allowing, not mandating, that a defendant bring counterclaims that require additional parties. Whether a party must be joined in an action continues to be governed only by Rule 19. Rule 13(a)(1)(B) does not transform Rule 20 into a mandatory joinder rule.

Requiring Ms. Pace to bring the claims against the individual defendants as a counterclaim in the initial action might well serve judicial economy, but the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure do not require such a result. The Rules strike a delicate balance between (1) a plaintiff’s interest in structuring litigation, (2) a defendant’s “wish to avoid multiple litigation, or inconsistent relief,” (3) an outsider’s interest in joining the litigation, and (4) “the interest of the courts and the public in complete, consistent, and efficient settlement of controversies.” The rules generally allow for a plaintiff to decide who to join in an action. A plaintiff’s interest in structuring litigation is overridden only when the prejudice to the defendant or an absent party is substantial and cannot be avoided. Otherwise, the threat of duplicative litigation generally is insufficient to override a plaintiff’s interest in this regard.

Indeed, if Ms. Pace had brought her claim before Timmermann’s filed suit, she could have chosen to file separate actions against Timmermann’s and the individual defendants. It makes little sense to require Ms. Pace to join the individual defendants under Rule 20 in order to bring all of her claims in the same action when, if she initially had been the plaintiff, she would not have been required to join those same parties.

Timmermann’s recognizes that Rule 20 does not require a litigant to join additional parties. Therefore, because a party is not required to join additional parties under Rules 13 or 20, the district court erred by barring Ms. Pace’s claims against the individual defendants and Mr. Pace’s claims for failing to join them when she brought her counterclaim.

B.

We turn now to whether the district court appropriately characterized Ms. Pace’s claim against Timmermann’s for abuse of process as a compulsory counterclaim. Ms. Pace submits that her abuse of process claim did not exist until there was “process” in the form of an information or indictment. She contends that the facts alleged in the 2013 complaint that occurred before she was charged only demonstrated one element of the claim, the defendants’ mens rea. “In order to be a compulsory counterclaim, Rule 13(a) requires that a claim exist at the time of pleading.” Thus, “a party need not assert a compulsory counterclaim if it has not matured when the party serves his answer.”

Although neither an indictment nor an arrest is a necessary element to bring an abuse of process claim under Illinois law, a plaintiff is required to plead some improper use of legal process. In most circumstances, this requirement is met through an arrest or physical seizure of property.

Ms. Pace was arrested on February 15, 2011. The company’s 2011 complaint was filed on March 3, 2011, and Ms. Pace filed her answer and counterclaim on April 5, 2011. Consequently, the only fact not in Ms. Pace’s possession at the time she filed her answer was the March 13, 2012 information. Illinois courts are clear, however, that an arrest is sufficient to bring an abuse of process claim. Ms. Pace’s abuse of process claim therefore matured when she was arrested, which occurred before she filed her responsive pleading. Her failure to raise the abuse of process claim as a counterclaim along with her answer therefore contravenes Rule 13.

Indeed, in alleging an abuse of process, Ms. Pace primarily relies on her 2011 arrest, and not on the fact that she was charged. The complaint alleges that the defendants intentionally injured and caused injury to Ms. Pace by giving “false information to law enforcement and explicitly or implicitly urging the arrest and/or the indictment of [Ms. Pace].” The complaint makes it clear that Ms. Pace could have brought her claim following her 2011 arrest, and thus, her abuse of process claim matured at that time.

Conclusion

We conclude that the district court erred in dismissing the Paces’ 2013 complaint in its entirety. Because neither Rule 13 nor Rule 20 provide for compulsory joinder, Ms. Pace’s claims against the individual defendants and Mr. Pace’s claims for loss of consortium were not compulsory counterclaims. Ms. Pace’s abuse of process claim against Timmermann’s was in existence when Ms. Pace filed her 2011 answer and counterclaim, and therefore the district court was correct to bar her subsequent abuse of process claim against Timmermann’s.

Crossclaims

Fed. R. Civ. P. Rule 13

(g) Crossclaim Against a Coparty. A pleading may state as a crossclaim any claim by one party against a coparty if the claim arises out of the transaction or occurrence that is the subject matter of the original action or of a counterclaim, or if the claim relates to any property that is the subject matter of the original action. The crossclaim may include a claim that the coparty is or may be liable to the crossclaimant for all or part of a claim asserted in the action against the crossclaimant.

(h) Joining Additional Parties. Rules 19 and 20 govern the addition of a person as a party to a counterclaim or crossclaim.

Kirkcaldy v. Richmond County Bd. of Ed., 212 F.R.D. 289 (M.D.N.C. 2002)

BEATY, District Judge.

This case comes before the Court on Defendant Richmond County Board of Education’s (“Board”) and Third-party Defendants Bruce Stanback, Sandy Lampley, Herman Williams, Myrtle Stogner, Mary Carroll, Jackson Dawkins, Carlene Hill, and Larry K. Weatherly’s (“Individual School Defendants”) Motion to Dismiss Defendant Marcus Smith’s (“Smith”) Cross-claim and Third-party Complaint. For the reasons stated below, the Motion to Dismiss is hereby GRANTED.

I. FACTUAL BACKGROUND

Until August of 2000, Smith served as a principal of the Leak Street Alternative School, part of the Richmond County School System overseen by the Board. On September 14, 2001, Plaintiff Elizabeth Kirkcaldy (“Kirkcaldy”), who had worked as a secretary at the Leak Street Alternative School, filed a lawsuit against Smith and the Board. Kirkcaldy’s Complaint alleges that from approximately July 20, 1999 to June 12, 2000, she was subjected to sexual harassment by Smith, who served as her direct supervisor during that time. Kirkcaldy claims that during this time, Smith repeatedly made unwelcome sexual contact with Kirkcaldy. Kirkcaldy also asserts that Smith frequently made comments of a sexual nature to her. Based on these facts, Kirkcaldy asserts the following claims: hostile work environment pursuant to 42 U.S.C. § 2000e et seq., intentional and negligent infliction of emotional distress against both the Board and Smith, and a claim for negligent supervision, retention and hiring against the Board.

In his Answer to Kirkcaldy’s Complaint, Smith brings a cross-claim against the Board and a third-party complaint against the Superintendent of the Richmond County School System, Larry K. Weatherly (“Weatherly”), and Board members Bruce Stanback, Sandy Lampley, Herman Williams, Myrtle Stogner, Mary Carroll, Jackson Dawkins, and Carlene Hill, all in their individual and official capacities. Smith’s claim against these Defendants is filed pursuant to 42 U.S.C. § 1983 based on the Individual School Defendants and the Board’s (together, “School Defendants”) alleged violation of Smith’s due process rights. It is this Section 1983 claim that the School Defendants now move to dismiss.

In support of his claim, Smith asserts the following alleged facts. On June 20, 2000, Weatherly informed Smith that he was being suspended with pay while Weatherly investigated the allegations of sexual harassment made by Kirkcaldy and another school employee, Sharon Renee Peek (“Peek”). Based upon the results of this investigation, on July 25, 2000, Weatherly changed Smith’s suspension with pay to suspension without pay. Weatherly also informed Smith that a hearing before the Board regarding Smith’s employment would be held in August of 2000. Weatherly further advised Smith that it would be recommended to the Board members that they terminate Smith from his position.

Prior to the Board hearing, which was held on August 24, 2000, Weatherly delivered to each Board member a copy of all the evidence he intended to present at the hearing against Smith. This evidence included references to polygraph examinations taken by Kirkcaldy and Peek. Smith asserts that this evidence was inadmissible at a school board hearing under North Carolina law. After reviewing the information provided to the Board members, including the references to the polygraph examinations, Myrtle Stogner, one of the Board members, allegedly made the statement to an unidentified individual that the case against Smith was ” cut and dried” and that he would be dismissed for the alleged conduct.

At the August 24, 2000 hearing, Smith was allowed to present his evidence. Smith proffered fourteen affidavits from witnesses that rebutted the allegations of harassment made against Smith. Smith also submitted his medical records and his wife’s affidavit demonstrating that he was impotent during the time period when the alleged harassment occurred, and therefore would have been physically unable to engage in some of the alleged misconduct. Smith requested a continuance of the hearing in order to obtain additional evidence concerning his impotence, but the Board denied his request.

At the conclusion of the August 24, 2000 hearing, the Board entered an order dismissing Smith from his position as principal. Smith appealed the Board’s decision dismissing him to the North Carolina Superior Court, which affirmed the Board’s decision. Smith then appealed the North Carolina Superior Court’s decision to the North Carolina Court of Appeals. This court affirmed the Superior Court’s decision, which upheld the Board’s decision to dismiss Smith.

Smith’s present cross-claim and third-party complaint filed pursuant to Section 1983 claims that the School Defendants violated his due process rights by denying him a fair hearing prior to his dismissal. In response, the School Defendants have filed the Motion to Dismiss now before the Court, asserting that dismissal of Smith’s cross-claim and third-party complaint is proper pursuant to Rule 12(b)(6) for failure to state a claim and Rule 12(b)(1) for lack of subject-matter jurisdiction.

II. DISCUSSION OF DEFENDANTS’ MOTION TO DISMISS

When a co-defendant asserts a cross-claim against a co-defendant, as Smith now asserts against the Board, the co-defendant’s cross-claim must meet the requirements of Rule 13(g). In relevant part, Rule 13(g) specifies that “a pleading may state as a cross-claim any claim by one party against a co-party arising out of the transaction or occurrence that is the subject matter either of the original action or of a counterclaim therein.” The Board asserts that Smith’s cross-claim does not qualify for joinder because the cross-claim does not arise out of the transaction or occurrence that is the subject of Kirkcaldy’s suit, namely, the incidents of harassment that she allegedly suffered, which ended on June 12, 2000. Rather, the Board maintains that Smith’s claim of a due process violation is based on the separate and different transaction or occurrence which involved the Board and Individual School Defendants’ conduct in preparing and conducting the August 24, 2000 hearing that resulted in Smith’s dismissal.

To determine whether Smith’s cross-claim arises out of the same transaction and occurrence as Kirkcaldy’s underlying claim, the Court refers to the Fourth Circuit case of Painter v. Harvey, 863 F.2d 329 (4th Cir.1988), in which the Fourth Circuit addressed this question, albeit in the context of a different subsection of Rule 13. The Fourth Circuit in Painter explained how to determine when a defendant’s claim was a compulsory counterclaim, as defined by Rule 13(a), to the claims alleged in the plaintiff’s complaint. Like the Rule 13(g) cross-claim determination that is the subject of this Court’s inquiry, the compulsory counterclaim determination under Rule 13(a) hinges on whether the claims arise from the same ” transaction and occurrence.” Accordingly, the Court finds that the Fourth Circuit’s definition of the phrase ” transaction and occurrence” in Rule 13(a) is directly relevant to the definition of the same term as used in Rule 13(g).

To determine if a cross-claim arose out of the same transaction or occurrence as the complaint, the Painter decision suggests conducting the following inquiries: (1) Are the issues of fact and law raised in the complaint and cross-claim largely the same? (2) Will substantially the same evidence support or refute the complaint as well as the cross-claim? (3) Is there any logical relationship between the complaint and the cross-claim? In considering these questions, the Court is mindful that these inquiries are guidelines and that it ” need not answer all these questions in the affirmative” in order to find that the claims alleged in Kirkcaldy’s Complaint and Smith’s cross-claim arise from the same transaction and occurrence.

Turning now to the first inquiry, which considers the identity of the issues of fact and law between the Complaint and the cross-claim, the Court recounts again that Kirkcaldy’s Complaint alleges the following causes of action: sexual harassment during the period of July 20, 1999 and June 12, 2000 in violation of 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(a), intentional and negligent infliction of emotional distress, and a claim of negligent supervision, retention, and hiring against the Board. In comparison, Smith asserts in his cross-claim that the Board violated his property interest in his employment and his reputation for honesty and morality when it terminated him without providing him with the due process required by law. More specifically, Smith asserts that his due process rights were violated because the Board members were biased against him and thus could not serve as impartial decision-makers. Smith further asserts that Weatherly, prior to the hearing, improperly presented the Board members with evidence gathered against Smith. Finally, Smith also alleges that the evidence used by Weatherly wrongly included references to Kirkcaldy and Peek’s polygraph results, which Smith alleges is prohibited by North Carolina law.

As the summary of the different counts asserted by Smith and Kirkcaldy demonstrate, Smith’s Section 1983 claim against the Board and the Individual School Defendants does not involve the same questions of fact and law as Kirkcaldy’s claims. With respect to the legal issues involved, Kirkcaldy’s claims will focus on the legal questions of whether Smith engaged in conduct that qualified as sexual harassment and intentional or negligent infliction of emotional distress and whether the Board, as Smith’s employer, should be held responsible for Smith’s actions. Smith’s claim, however, focuses on whether the Board violated his due process rights during his suspension hearing. The legal questions presented by Smith’s claim therefore would overlap very little, if at all, with Kirkcaldy’s claims. With respect to whether there are common questions of fact, Kirkcaldy’s claims and Smith’s claim again would diverge. While the factfinder in Kirkcaldy’s action will be asked to determine whether Smith actually sexually harassed Kirkcaldy during her employment from July 20, 1999 through June 12, 2000, the factfinder for Smith’s claims must decide whether the Board’s actions at the August 24, 2000 hearing, based on the information known to the Board at that time, violated Smith’s due process rights. Although it is true that the same persons might be witnesses in both cases, Smith and Kirkcaldy’s use of these witnesses will differ because their questions will be focused on different periods of time and different legal theories. This inquiry therefore suggests that Kirkcaldy and Smith’s claims are not part of the same transaction or occurrence.

The Court now turns to the second inquiry, which asks whether the same evidence can support both Kirkcaldy’s claims and Smith’s cross-claim. Again, the Court finds that this consideration counsels against joining Smith’s cross-claim to the original lawsuit. As already mentioned, Smith’s case will focus upon the Board’s treatment of him during its investigation and at the August 24, 2000 hearing in order to demonstrate the alleged bias of the Board members and Weatherly. Smith’s evidence, therefore, will likely include a reference to the evidence that Weatherly gathered against him in investigating Kirkcaldy’s and Peek’s claims. Smith, of course, would contend that this evidence was improperly presented to the Board members prior to the August 24, 2000 Board meeting so as to deny Smith due process. Kirkcaldy, on the other hand, will not utilize the evidence regarding the occurrences at and immediately prior to the August 24, 2000 Board meeting. Instead, Kirkcaldy’s proof will focus on testimony and other evidence regarding Smith’s allegedly harassing treatment of her during the period of July 20, 1999 through June 12, 2000. The lack of evidentiary overlap between these claims leads the Court to conclude that this inquiry also suggests that Smith’s claim is not part of the same transaction and occurrence as Kirkcaldy’s claims.

Although the first two inquiries suggest that Smith’s claim does not rely on the same evidence, facts, or law as Kirkcaldy’s claims and therefore the claims are not part of the same transaction or occurrence, the Court is cognizant that some cross-claims may still be part of the same transaction or occurrence as the underlying action ” even though they do not involve a substantial identity of evidence with the claim.” Accordingly, despite the Court’s finding regarding the first two inquiries, Smith’s claim could still be part of the same transaction or occurrence as Kirkcaldy’s action if it satisfies the third inquiry by demonstrating that it possesses a strong logical relationship to Kirkcaldy’s action. The Court recognizes that the claims alleged by Smith and Kirkcaldy are necessarily related to some extent in a causal and chronological way, because Kirkcaldy’s claims of sexual harassment were part of the evidence that the Board considered in reaching its decision to terminate Smith. However, Kirkcaldy’s action will focus on what occurred between her and Smith, and the extent that the Board knew of the behavior or the potential of such behavior prior to its dismissal of Smith. This inquiry is logically attenuated from Smith’s claims against the Board, which depends on whether the Board provided the necessary due process to Smith when they decided to terminate him from his position.

The weak logical relationship between these claims is demonstrated by the potential confusion a fact-finder might face if forced to hear the two cases together. Kirkcaldy’s action will require the fact-finder to determine whether Smith sexually harassed Kirkcaldy. However, the fact-finder would need to switch its focus when considering Smith’s cross-claim, for then the fact-finder must decide, irregardless of whether Kirkcaldy’s claims of sexual harassment were in fact true, if the Board violated Smith’s due process rights when it made its decision to terminate him. In light of the potential for confusion and given the different facts involved in Kirkcaldy and Smith’s claims, the Court finds that the logical relationship between Kirkcaldy’s Complaint and Smith’s cross-claim is not strong enough to justify combining Smith’s claims of due process violations with Kirkcaldy’s claims of sexual harassment. The Court therefore concludes that Smith’s claim against the School Board is not part of the same transaction and occurrence as Kirkcaldy’s claims and therefore does not meet Rule 13(g)’s requirements.

Notwithstanding the Court’s determination that Smith’s cross-claim does not satisfy the requirements of Rule 13(g) because it does not arise from the same transaction or occurrence as Kirkcaldy’s claims, Smith argues that his claim against the Board also qualifies for jurisdiction as a permissive counterclaim that is authorized by Rule 13(b). Pursuant to Rule 13(b), a party may state, as a counterclaim against an opposing party, any claim that is ” not arising out of the transaction or occurrence that is the subject matter of the opposing party’s claim.” The Board and Smith were originally co-defendants, and co-defendants do not qualify as opposing parties for the purposes of Rule 13(b). Smith argues, however, that when the Board brought its cross-claim against Smith for indemnification and contribution, the Board became an opposing party against whom Smith may bring an unrelated claim. The success of Smith’s argument thus hinges on whether a cross-claim for indemnity by a co-defendant transforms the two co-defendants into opposing parties for whom the Rules regarding compulsory and permissive counterclaims apply.

Although the Federal Rules do not themselves address when a co-defendant becomes an opposing party, the majority of courts ruling on this issue have accepted the general premise that the term “opposing party” includes co-defendants once a substantive cross-claim is filed by one co-defendant against the other. However, and particularly relevant to the case at hand, several courts have suggested that a co-defendant does not become an opposing party if the cross-claim asserted by the other co-defendant is merely a claim of indemnity or contribution instead of a substantive claim. Such a limitation is warranted because a cross-claim for indemnity or contribution “would not introduce new issues into the case, and could, in all likelihood, be litigated without substantially increasing the cost or complexity of the litigation.” The Court finds that this analysis of when cross-defendants become opposing parties best furthers the purpose of the Federal Rules to “dispose of the entire subject matter arising from one set of facts in one action, thus administering complete and evenhanded justice expeditiously and economically.” Accordingly, as the Board’s cross-claim consists only of a claim for indemnification and contribution, the Court finds that the Board’s cross-claim does not provide Smith with the opposing party status needed pursuant to Rule 13(b) to assert a permissive counterclaim. Without such status, Smith’s claims against the School Board do not qualify for inclusion with the instant case pursuant to the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure and the Court shall therefore grant, without prejudice, the School Board’s Motion to dismiss Smith’s claims for lack of subject-matter jurisdiction.

Parties

Permissive Party Joinder

Fed. R. Civ. P. Rule 20

(a) Persons Who May Join or Be Joined.

(1) Plaintiffs. Persons may join in one action as plaintiffs if:

(A) they assert any right to relief jointly, severally, or in the alternative with respect to or arising out of the same transaction, occurrence, or series of transactions or occurrences; and

(B) any question of law or fact common to all plaintiffs will arise in the action.

(2) Defendants. Persons—as well as a vessel, cargo, or other property subject to admiralty process in rem—may be joined in one action as defendants if:

(A) any right to relief is asserted against them jointly, severally, or in the alternative with respect to or arising out of the same transaction, occurrence, or series of transactions or occurrences; and

(B) any question of law or fact common to all defendants will arise in the action.

(3) Extent of Relief. Neither a plaintiff nor a defendant need be interested in obtaining or defending against all the relief demanded. The court may grant judgment to one or more plaintiffs according to their rights, and against one or more defendants according to their liabilities.

(b) Protective Measures. The court may issue orders—including an order for separate trials—to protect a party against embarrassment, delay, expense, or other prejudice that arises from including a person against whom the party asserts no claim and who asserts no claim against the party.

Mosley v. General Motors, 497 F. 2d 1330 (8th Cir. 1974)

ROSS, Circuit Judge

Nathaniel Mosley and nine other persons joined in bringing this action individually and as class representatives alleging that their rights guaranteed under 42 U.S.C. § 2000e et seq. and 42 U.S.C. § 1981 were denied by General Motors and Local 25, United Automobile, Aerospace and Agriculture Implement Workers of America Union by reason of their color and race. Each of the ten named plaintiffs had, prior to the filing of the complaint, filed a charge with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission EEOC asserting the facts underlying these claims. Pursuant thereto, the EEOC made a reasonable cause finding that General Motors, Fisher Body Division and Chevrolet Division, and the Union had engaged in unlawful employment practices in violation of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Accordingly, the charging parties were notified by EEOC of their right to institute a civil action in the appropriate federal district court, pursuant to § 706(e) of Title VII, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(e).

In each of the first eight counts of the twelve-count complaint, eight of the ten plaintiffs alleged that General Motors, Chevrolet Division, had engaged in unlawful employment practices by: “discriminating against Negroes as regards promotions, terms and conditions of employment”; “retaliating against Negro employees who protested actions made unlawful by Title VII of the Act and by discharging some because they protested said unlawful acts”; “failing to hire Negro employees as a class on the basis of race”; “failing to hire females as a class on the basis of sex”; “discharging Negro employees on the basis of race”; and “discriminating against Negroes and females in the granting of relief time.” Each additionally charged that the defendant Union had engaged in unlawful employment practices “with respect to the granting of relief time to Negro and female employees” and “by failing to pursue 6a grievances.” The remaining two plaintiffs made similar allegations against General Motors, Fisher Body Division. All of the individual plaintiffs requested injunctive relief, back pay, attorneys fees and costs.

The district court ordered that “insofar as the first ten counts are concerned, those ten counts shall be severed into ten separate causes of action,” and each plaintiff was directed to bring a separate action based upon his complaint, duly and separately filed.

In reaching this conclusion on joinder, the district court followed the reasoning of Smith v. North American Rockwell Corp., 50 F.R.D. 515 (N.D.Okla.1970), which, in a somewhat analogous situation, found there was no right to relief arising out of the same transaction, occurrence or series of transactions or occurrences, and that there was no question of law or fact common to all plaintiffs sufficient to sustain joinder under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 20(a). Similarly, the district court here felt that the plaintiffs’ joint actions against General Motors and the Union presented a variety of issues having little relationship to one another; that they had only one common problem, i. e. the defendant; and that as pleaded the joint actions were completely unmanageable. Upon entering the order, and upon application of the plaintiffs, the district court found that its decision involved a controlling question of law as to which there is a substantial ground for difference of opinion and that any of the parties might make application for appeal under 28 U.S.C. § 1292(b). We granted the application to permit this interlocutory appeal and for the following reasons we affirm in part and reverse in part.

Rule 20(a) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure provides:

All persons may join in one action as plaintiffs if they assert any right to relief jointly, severally, or in the alternative in respect of or arising out of the same transaction, occurrence, or series of transactions or occurrences and if any question of law or fact common to all these persons will arise in the action.

Additionally, Rule 20(b) and Rule 42(b) vest in the district court the discretion to order separate trials or make such other orders as will prevent delay or prejudice. In this manner, the scope of the civil action is made a matter for the discretion of the district court, and a determination on the question of joinder of parties will be reversed on appeal only upon a showing of abuse of that discretion. To determine whether the district court’s order was proper herein, we must look to the policy and law that have developed around the operation of Rule 20.

The purpose of the rule is to promote trial convenience and expedite the final determination of disputes, thereby preventing multiple lawsuits. Single trials generally tend to lessen the delay, expense and inconvenience to all concerned. Reflecting this policy, the Supreme Court has said:

Under the Rules, the impulse is toward entertaining the broadest possible scope of action consistent with fairness to the parties; joinder of claims, parties and remedies is strongly encouraged.

United Mine Workers of America v. Gibbs, 383 U.S. 715 (1966).

Permissive joinder is not, however, applicable in all cases. The rule imposes two specific requisites to the joinder of parties: (1) a right to relief must be asserted by, or against, each plaintiff or defendant relating to or arising out of the same transaction or occurrence, or series of transactions or occurrences; and (2) some question of law or fact common to all the parties must arise in the action.

In ascertaining whether a particular factual situation constitutes a single transaction or occurrence for purposes of Rule 20, a case by case approach is generally pursued. No hard and fast rules have been established under the rule. However, construction of the terms “transaction or occurrence” as used in the context of Rule 13(a) counterclaims offers some guide to the application of this test. For the purposes of the latter rule,

“Transaction” is a word of flexible meaning. It may comprehend a series of many occurrences, depending not so much upon the immediateness of their connection as upon their logical relationship.

Moore v. New York Cotton Exchange, 270 U.S. 593 (1926). Accordingly, all “logically related” events entitling a person to institute a legal action against another generally are regarded as comprising a transaction or occurrence. The analogous interpretation of the terms as used in Rule 20 would permit all reasonably related claims for relief by or against different parties to be tried in a single proceeding. Absolute identity of all events is unnecessary.

This construction accords with the result reached in United States v. Mississippi, 380 U.S. 128 (1965), a suit brought by the United States against the State of Mississippi, the election commissioners, and six voting registrars of the State, charging them with engaging in acts and practices hampering and destroying the right of black citizens of Mississippi to vote. The district court concluded that the complaint improperly attempted to hold the six county registrars jointly liable for what amounted to nothing more than individual torts committed by them separately against separate applicants. In reversing, the Supreme Court said:

But the complaint charged that the registrars had acted and were continuing to act as part of a state-wide system designed to enforce the registration laws in a way that would inevitably deprive colored people of the right to vote solely because of their color. On such an allegation the joinder of all the registrars as defendants in a single suit is authorized by Rule 20(a) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. These registrars were alleged to be carrying on activities which were part of a series of transactions or occurrences the validity of which depended to a large extent upon “questions of law or fact common to all of them.”

Id. at 142-143.

Here too, then, the plaintiffs have asserted a right to relief arising out of the same transactions or occurrences. Each of the ten plaintiffs alleged that he had been injured by the same general policy of discrimination on the part of General Motors and the Union. Since a “state-wide system designed to enforce the registration laws in a way that would inevitably deprive colored people of the right to vote” was determined to arise out of the same series of transactions or occurrences, we conclude that a company-wide policy purportedly designed to discriminate against blacks in employment similarly arises out of the same series of transactions or occurrences. Thus the plaintiffs meet the first requisite for joinder under Rule 20(a).

The second requisite necessary to sustain a permissive joinder under the rule is that a question of law or fact common to all the parties will arise in the action. The rule does not require that all questions of law and fact raised by the dispute be common. Yet, neither does it establish any qualitative or quantitative test of commonality. For this reason, cases construing the parallel requirement under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 23(a) provide a helpful framework for construction of the commonality required by Rule 20. In general, those cases that have focused on Rule 23(a)(2) have given it a permissive application so that common questions have been found to exist in a wide range of context. Specifically, with respect to employment discrimination cases under Title VII, courts have found that the discriminatory character of a defendant’s conduct is basic to the class, and the fact that the individual class members may have suffered different effects from the alleged discrimination is immaterial for the purposes of the prerequisite. In this vein, one court has said:

Although the actual effects of a discriminatory policy may thus vary throughout the class, the existence of the discriminatory policy threatens the entire class. And whether the Damoclean threat of a racially discriminatory policy hangs over the racial class is a question of fact common to all the members of the class.

The right to relief here depends on the ability to demonstrate that each of the plaintiffs was wronged by racially discriminatory policies on the part of the defendants General Motors and the Union. The discriminatory character of the defendants’ conduct is thus basic to each plaintiff’s recovery. The fact that each plaintiff may have suffered different effects from the alleged discrimination is immaterial for the purposes of determining the common question of law or fact. Thus, we conclude that the second requisite for joinder under Rule 20(a) is also met by the complaint.

For the reasons set forth above, we conclude that the district court abused its discretion in severing the joined actions. The difficulties in ultimately adjudicating damages to the various plaintiffs are not so overwhelming as to require such severance. If appropriate, separate trials may be granted as to any particular issue after the determination of common questions.

The judgment of the district court disallowing joinder of the plaintiffs’ individual actions is reversed and remanded with directions to permit the plaintiffs to proceed jointly.

Third-Party Joinder

Fed. R. Civ. P. Rule 14

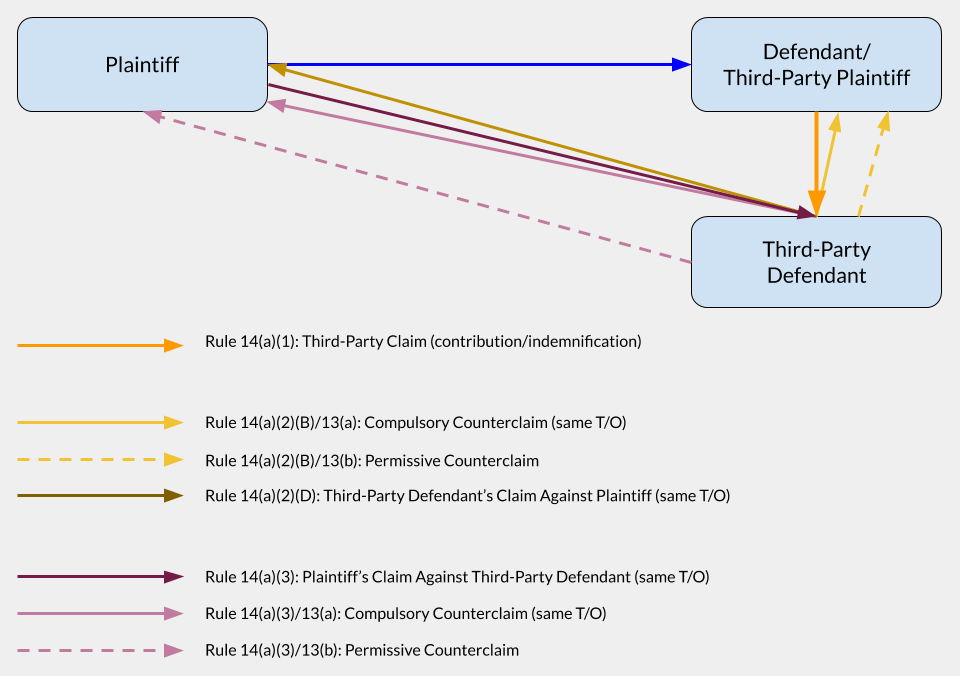

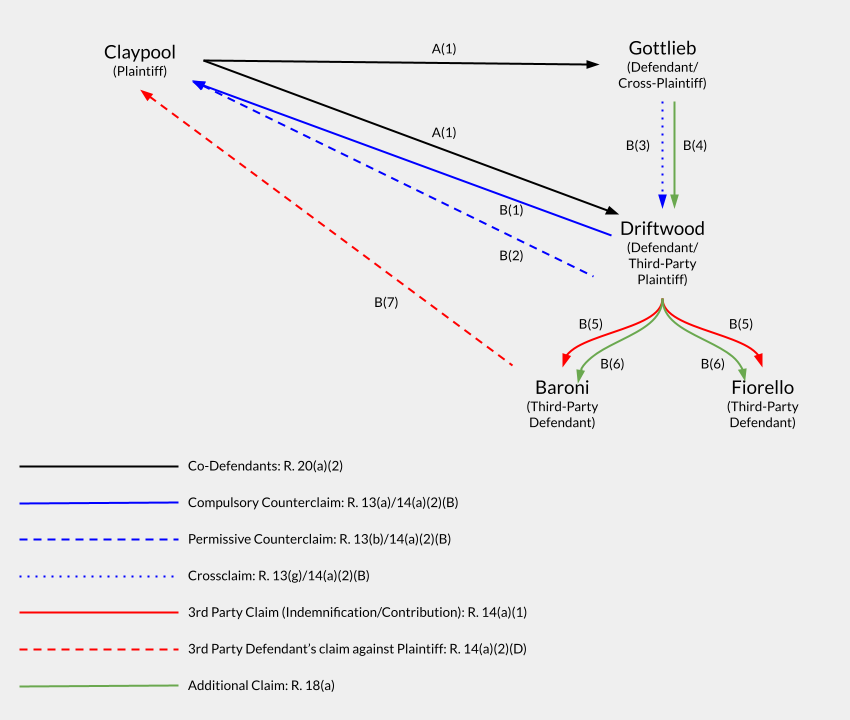

(a) When a Defending Party May Bring in a Third Party.

(1) Timing of the Summons and Complaint. A defending party may, as third-party plaintiff, serve a summons and complaint on a nonparty who is or may be liable to it for all or part of the claim against it. But the third-party plaintiff must, by motion, obtain the court’s leave if it files the third-party complaint more than 14 days after serving its original answer.

(2) Third-Party Defendant’s Claims and Defenses. The person served with the summons and third-party complaint—the “third-party defendant”:

(A) must assert any defense against the third-party plaintiff’s claim under Rule 12;

(B) must assert any counterclaim against the third-party plaintiff under Rule 13(a), and may assert any counterclaim against the third-party plaintiff under Rule 13(b) or any crossclaim against another third-party defendant under Rule 13(g);

(C) may assert against the plaintiff any defense that the third-party plaintiff has to the plaintiff’s claim; and

(D) may also assert against the plaintiff any claim arising out of the transaction or occurrence that is the subject matter of the plaintiff’s claim against the third-party plaintiff.

(3) Plaintiff’s Claims Against a Third-Party Defendant. The plaintiff may assert against the third-party defendant any claim arising out of the transaction or occurrence that is the subject matter of the plaintiff’s claim against the third-party plaintiff. The third-party defendant must then assert any defense under Rule 12 and any counterclaim under Rule 13(a), and may assert any counterclaim under Rule 13(b) or any crossclaim under Rule 13(g).

(4) Motion to Strike, Sever, or Try Separately. Any party may move to strike the third-party claim, to sever it, or to try it separately.

(5) Third-Party Defendant’s Claim Against a Nonparty. A third-party defendant may proceed under this rule against a nonparty who is or may be liable to the third-party defendant for all or part of any claim against it.

(b) When a Plaintiff May Bring in a Third Party. When a claim is asserted against a plaintiff, the plaintiff may bring in a third party if this rule would allow a defendant to do so.

Lehman v. Revolution Portfolio, 166 F.3d 389 (1st Cir. 1999)

SELYA, Circuit Judge

This appeal grows out of a triangular 1987 financial transaction that involved the Farm Street Trust (the Trust), its beneficiaries (Barry Lehman and Stuart A. Roffman), and First Mutual Bank for Savings (the Bank). In the ensuing eleven years, the transaction imploded, litigation commenced, the Bank and Lehman became insolvent, parties came and went, and the case was closed and partially reopened. In the end, only a third-party complaint proved ripe for adjudication. Even then, the district court dismissed two of its three counts, but entered summary judgment on the remaining count. The third-party defendant, Roffman, now appeals. After sorting through the muddled record and the case’s serpentine procedural history, we affirm.

I. BACKGROUND

The historical facts are not seriously disputed. On or about October 19, 1987, the Trust, acting through its trustee, executed a promissory note for $2,800,000 in favor of the Bank in order to fund the purchase of property in Dover, Massachusetts. Lehman and Roffman, each of whom enjoyed a 50% beneficial interest in the Trust, personally guaranteed the note, and Lehman proffered two parcels of real estate as additional collateral. In short order, the Trust defaulted on the loan and the Bank foreclosed on Lehman’s properties. Lehman responded by suing the Bank seeking restraint or rescission of the imminent sale of his real estate. The gravamen of his suit was a claim that Roffman had fraudulently introduced a sham investor to the Bank in order to gull it into making the loan, and that the Bank, in swallowing this spurious bait hook, line, and sinker, had failed to exercise due diligence.

[The Bank failed and was placed in receivership. The FDIC, in its role as receiver, replaced the Bank as defendant and asserted a counterclaim against Lehman, as guarantor on the loan, to collect the outstanding balance owed. The FDIC also joined Roffman as a third-party defendant.]

The FDIC’s third-party complaint contained three counts. The first two sought indemnification and contribution, respectively, in regard to the claims advanced by Lehman. The third sought judgment against Roffman, qua guarantor, for the outstanding loan balance.

[Roffman moved to strike the third-party complaint. The trial court denied that motion and Roffman appealed. Meanwhile, Revolution Portfolio LLC (“RP”), to which the FDIC had assigned its interest in the Farm Street Trust debt, replaced the FDIC as the real party in interest.]

II. Discussion