Personal Jurisdiction

Constitutional Limits: Due Process

U.S. Constitution

Amendment V

No person shall … be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; ….

Amendment XIV, sec. 1

… nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; ….

Foundations

Pennoyer v. Neff, 95 U.S. 714 (1877)

MR. JUSTICE FIELD delivered the opinion of the court.

This is an action to recover the possession of a tract of land, of the alleged value of $15,000, situated in the State of Oregon. The plaintiff asserts title to the premises by a patent of the United States issued to him in 1866, under the act of Congress of Sept. 27, 1850, usually known as the Donation Law of Oregon. The defendant claims to have acquired the premises under a sheriff’s deed, made upon a sale of the property on execution issued upon a judgment recovered against the plaintiff in one of the circuit courts of the State. The case turns upon the validity of this judgment.

It appears from the record that the judgment was rendered in February, 1866, in favor of J.H. Mitchell, for less than $300, including costs, in an action brought by him upon a demand for services as an attorney; that, at the time the action was commenced and the judgment rendered, the defendant therein, the plaintiff here, was a non-resident of the State; that he was not personally served with process, and did not appear therein; and that the judgment was entered upon his default in not answering the complaint, upon a constructive service of summons by publication.

The Code of Oregon provides for such service when an action is

brought against a non-resident and absent defendant, who has property

within the State. It also provides, where the action is for the recovery

of money or damages, for the attachment of the property of the

non-resident. And it also declares that no natural person is subject to

the jurisdiction of a court of the State, “unless he appear in the

court, or be found within the State, or be a resident thereof, or have

property therein; and, in the last case, only to the extent of such

property at the time the jurisdiction attached.” Construing this latter

provision to mean, that, in an action for money or damages where a

defendant does not appear in the court, and is not found within the

State, and is not a resident thereof, but has property therein, the

jurisdiction of the court extends only over such property, the

declaration expresses a principle of general, if not universal, law. The

authority of every tribunal is necessarily restricted by the territorial

limits of the State in which it is established. Any attempt to exercise

authority beyond those limits would be deemed in every other forum, as

has been said by this court, an illegitimate assumption of power, and be

resisted as mere abuse. In the case against the plaintiff, the property

here in controversy sold under the judgment rendered was not attached,

nor in any way brought under the jurisdiction of the court. Its first

connection with the case was caused by a levy of the execution. It was

not, therefore, disposed of pursuant to any adjudication, but only in

enforcement of a personal judgment, having no relation to the property,

rendered against a non-resident without service of process upon him in

the action, or his appearance therein. The court below did not consider

that an attachment of the property was essential to its jurisdiction or

to the validity of the sale, but held that the judgment was invalid from

defects in the affidavitThe Supreme Court held that a challenge to the form

of the affidavit could only be raised on a direct appeal, not a

collateral attack.

upon which the order of publication was obtained, and in

the affidavit by which the publication was proved.

It was also contended in that court, and is insisted upon here, that

the judgment in the State court against the plaintiff was void for want

of personal service of process on him, or of his appearance in the

action in which it was rendered, and that the premises in controversy

could not be subjected to the payment of the demand of a resident

creditor except by a proceeding in rem;“In-rem jurisdiction refers to the power of a court

over an item of real or personal property. The”thing” over which the

court has power may be a piece of land or even a marriage. Thus, a court

with only in-rem jurisdiction may terminate a marriage or declare who

owns a piece of land. In-rem jurisdiction is based on the location of

the property and enforcement follows property rather than person.” Wex Legal

Dictionary.

that is, by a direct proceeding against the property for

that purpose. If these positions are sound, the ruling of the Circuit

Court as to the invalidity of that judgment must be sustained,

notwithstanding our dissent from the reasons upon which it was made. And

that they are sound would seem to follow from two well-established

principles of public law respecting the jurisdiction of an independent

State over persons and property. The several States of the Union are

not, it is true, in every respect independent, many of the rights and

powers which originally belonged to them being now vested in the

government created by the Constitution. But, except as restrained and

limited by that instrument, they possess and exercise the authority of

independent States, and the principles of public law to which we have

referred are applicable to them. One of these principles is, that every

State possesses exclusive jurisdiction and sovereignty over persons and

property within its territory. As a consequence, every State has the

power to determine for itself the civil status and capacities of its

inhabitants; to prescribe the subjects upon which they may contract, the

forms and solemnities with which their contracts shall be executed, the

rights and obligations arising from them, and the mode in which their

validity shall be determined and their obligations enforced; and also to

regulate the manner and conditions upon which property situated within

such territory, both personal and real, may be acquired, enjoyed, and

transferred. The other principle of public law referred to follows from

the one mentioned; that is, that no State can exercise direct

jurisdiction and authority over persons or property without its

territory. The several States are of equal dignity and authority, and

the independence of one implies the exclusion of power from all others.

And so it is laid down by jurists, as an elementary principle, that the

laws of one State have no operation outside of its territory, except so

far as is allowed by comity; and that no tribunal established by it can

extend its process beyond that territory so as to subject either persons

or property to its decisions.

But as contracts made in one State may be enforceable only in another State, and property may be held by non-residents, the exercise of the jurisdiction which every State is admitted to possess over persons and property within its own territory will often affect persons and property without it. To any influence exerted in this way by a State affecting persons resident or property situated elsewhere, no objection can be justly taken; whilst any direct exertion of authority upon them, in an attempt to give ex-territorial operation to its laws, or to enforce an ex-territorial jurisdiction by its tribunals, would be deemed an encroachment upon the independence of the State in which the persons are domiciled or the property is situated, and be resisted as usurpation.

Thus the State, through its tribunals, may compel persons domiciled within its limits to execute, in pursuance of their contracts respecting property elsewhere situated, instruments in such form and with such solemnities as to transfer the title, so far as such formalities can be complied with; and the exercise of this jurisdiction in no manner interferes with the supreme control over the property by the State within which it is situated.

So the State, through its tribunals, may subject property situated within its limits owned by non-residents to the payment of the demand of its own citizens against them; and the exercise of this jurisdiction in no respect infringes upon the sovereignty of the State where the owners are domiciled. Every State owes protection to its own citizens; and, when non-residents deal with them, it is a legitimate and just exercise of authority to hold and appropriate any property owned by such non-residents to satisfy the claims of its citizens. It is in virtue of the State’s jurisdiction over the property of the non-resident situated within its limits that its tribunals can inquire into that non-resident’s obligations to its own citizens, and the inquiry can then be carried only to the extent necessary to control the disposition of the property. If the non-resident have no property in the State, there is nothing upon which the tribunals can adjudicate.

If, without personal service, judgments in personam,“In personam refers to courts’ power to adjudicate

matters directed against a party, as distinguished from in-rem

proceedings over disputed property.” Wex Legal

Dictionary.

obtained ex parte“In civil procedure, ex parte is used to refer to

motions for orders that can be granted without waiting for a response

from the other side. Generally, these are orders that are only in place

until further hearings can be held, such as a temporary restraining

order.

Typically, a court will be hesitant to make an ex parte

motion. This is because the Fifth Amendment and the Fourteenth Amendment

guarantee a right to due process, and ex parte motions—due to their

exclusion of one party—risk violating the excluded party’s right to due

process.” Wex Legal

Dictionary.

against non-residents and absent parties, upon mere

publication of process, which, in the great majority of cases, would

never be seen by the parties interested, could be upheld and enforced,

they would be the constant instruments of fraud and oppression.

Judgments for all sorts of claims upon contracts and for torts, real or

pretended, would be thus obtained, under which property would be seized,

when the evidence of the transactions upon which they were founded, if

they ever had any existence, had perished.

Substituted service by publication, or in any other authorized form, may be sufficient to inform parties of the object of proceedings taken where property is once brought under the control of the court by seizure or some equivalent act. The law assumes that property is always in the possession of its owner, in person or by agent; and it proceeds upon the theory that its seizure will inform him, not only that it is taken into the custody of the court, but that he must look to any proceedings authorized by law upon such seizure for its condemnation and sale. Such service may also be sufficient in cases where the object of the action is to reach and dispose of property in the State, or of some interest therein, by enforcing a contract or a lien respecting the same, or to partition it among different owners, or, when the public is a party, to condemn and appropriate it for a public purpose. In other words, such service may answer in all actions which are substantially proceedings in rem. But where the entire object of the action is to determine the personal rights and obligations of the defendants, that is, where the suit is merely in personam, constructive service in this form upon a non-resident is ineffectual for any purpose. Process from the tribunals of one State cannot run into another State, and summon parties there domiciled to leave its territory and respond to proceedings against them. Publication of process or notice within the State where the tribunal sits cannot create any greater obligation upon the non-resident to appear. Process sent to him out of the State, and process published within it, are equally unavailing in proceedings to establish his personal liability.

The want of authority of the tribunals of a State to adjudicate upon the obligations of non-residents, where they have no property within its limits, is not denied by the court below: but the position is assumed, that, where they have property within the State, it is immaterial whether the property is in the first instance brought under the control of the court by attachment or some other equivalent act, and afterwards applied by its judgment to the satisfaction of demands against its owner; or such demands be first established in a personal action, and the property of the non-resident be afterwards seized and sold on execution. But the answer to this position has already been given in the statement, that the jurisdiction of the court to inquire into and determine his obligations at all is only incidental to its jurisdiction over the property. Its jurisdiction in that respect cannot be made to depend upon facts to be ascertained after it has tried the cause and rendered the judgment. If the judgment be previously void, it will not become valid by the subsequent discovery of property of the defendant, or by his subsequent acquisition of it. The judgment if void when rendered, will always remain void: it cannot occupy the doubtful position of being valid if property be found, and void if there be none. Even if the position assumed were confined to cases where the non-resident defendant possessed property in the State at the commencement of the action, it would still make the validity of the proceedings and judgment depend upon the question whether, before the levy of the execution, the defendant had or had not disposed of the property. If before the levy the property should be sold, then, according to this position, the judgment would not be binding. This doctrine would introduce a new element of uncertainty in judicial proceedings. The contrary is the law: the validity of every judgment depends upon the jurisdiction of the court before it is rendered, not upon what may occur subsequently.

The force and effect of judgments rendered against non-residents without personal service of process upon them, or their voluntary appearance, have been the subject of frequent consideration in the courts of the United States and of the several States, as attempts have been made to enforce such judgments in States other than those in which they were rendered, under the provision of the Constitution requiring that “full faith and credit shall be given in each State to the public acts, records, and judicial proceedings of every other State;” and the act of Congress providing for the mode of authenticating such acts, records, and proceedings, and declaring that, when thus authenticated, “they shall have such faith and credit given to them in every court within the United States as they have by law or usage in the courts of the State from which they are or shall be taken.” In the earlier cases, it was supposed that the act gave to all judgments the same effect in other States which they had by law in the State where rendered. But this view was afterwards qualified so as to make the act applicable only when the court rendering the judgment had jurisdiction of the parties and of the subject-matter, and not to preclude an inquiry into the jurisdiction of the court in which the judgment was rendered, or the right of the State itself to exercise authority over the person or the subject-matter.

Be that as it may, the courts of the United States are not required to give effect to judgments of this character when any right is claimed under them. Whilst they are not foreign tribunals in their relations to the State courts, they are tribunals of a different sovereignty, exercising a distinct and independent jurisdiction, and are bound to give to the judgments of the State courts only the same faith and credit which the courts of another State are bound to give to them.

Since the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Federal Constitution, the validity of such judgments may be directly questioned, and their enforcement in the State resisted, on the ground that proceedings in a court of justice to determine the personal rights and obligations of parties over whom that court has no jurisdiction do not constitute due process of law. Whatever difficulty may be experienced in giving to those terms a definition which will embrace every permissible exertion of power affecting private rights, and exclude such as is forbidden, there can be no doubt of their meaning when applied to judicial proceedings. They then mean a course of legal proceedings according to those rules and principles which have been established in our systems of jurisprudence for the protection and enforcement of private rights. To give such proceedings any validity, there must be a tribunal competent by its constitution—that is, by the law of its creation—to pass upon the subject-matter of the suit; and, if that involves merely a determination of the personal liability of the defendant, he must be brought within its jurisdiction by service of process within the State, or his voluntary appearance.

Except in cases affecting the personal status of the plaintiff, and

cases in which that mode of service may be considered to have been

assented to in advance,In an omitted portion of the opinion, the Court notes

some limits to its holding. In suits “to determine the civil status and

capacities of” state residents (e.g. divorce cases) judgments may bind

non-residents even “without personal service of process or personal

notice”. States may also require that non-residents appoint in-state

agents to receive service, or consent to alternative forms of service,

in cases involving business dealings or contracts within the

state.

as hereinafter mentioned, the substituted service of

process by publication, allowed by the law of Oregon and by similar laws

in other States, where actions are brought against non-residents, is

effectual only where, in connection with process against the person for

commencing the action, property in the State is brought under the

control of the court, and subjected to its disposition by process

adapted to that purpose, or where the judgment is sought as a means of

reaching such property or affecting some interest therein; in other

words, where the action is in the nature of a proceeding in

rem.

It is true that, in a strict sense, a proceeding in rem is one taken directly against property, and has for its object the disposition of the property, without reference to the title of individual claimants; but, in a larger and more general sense, the terms are applied to actions between parties, where the direct object is to reach and dispose of property owned by them, or of some interest therein. Such are cases commenced by attachment against the property of debtors, or instituted to partition real estate, foreclose a mortgage, or enforce a lien. So far as they affect property in the State, they are substantially proceedings in rem in the broader sense which we have mentioned.

It follows from the views expressed that the personal judgment recovered in the State court of Oregon against the plaintiff herein, then a non-resident of the State, was without any validity, and did not authorize a sale of the property in controversy.

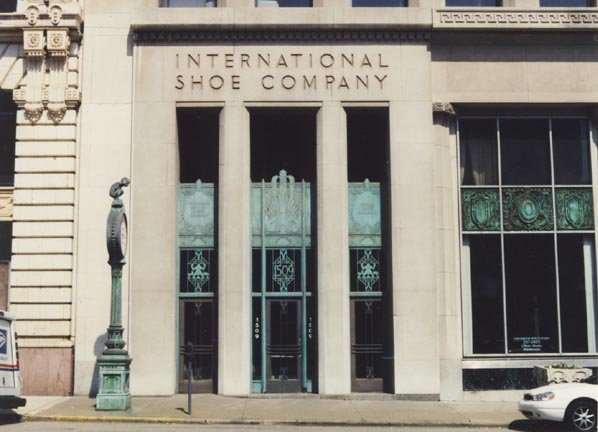

International Shoe Corp. v. Washington, 326 U.S. 310 (1945)

Chief Justice STONE delivered the opinion of the Court.

The questions for decision are (1) whether, within the limitations of the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, appellant, a Delaware corporation, has by its activities in the State of Washington rendered itself amenable to proceedings in the courts of that state to recover unpaid contributions to the state unemployment compensation fund exacted by state statutes, and (2) whether the state can exact those contributions consistently with the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

In this case notice of assessment for unpaid contributions for the

years in question was personally served upon a sales solicitor employed

by appellant in the State of Washington, and a copy of the notice was

mailed by registered mail to appellant at its address in St. Louis,

Missouri.

International

Shoe Co., St. Louis, Missouri Appellant appeared specially before

the office of unemployment and moved to set aside the order and notice

of assessment on the ground that the service upon appellant’s salesman

was not proper service upon appellant; that appellant was not a

corporation of the State of Washington and was not doing business within

the state; that it had no agent within the state upon whom service could

be made; and that appellant is not an employer and does not furnish

employment within the meaning of the statute.

The facts as found by the appeal tribunal and accepted by the state Superior Court and Supreme Court, are not in dispute. Appellant is a Delaware corporation, having its principal place of business in St. Louis, Missouri, and is engaged in the manufacture and sale of shoes and other footwear. It maintains places of business in several states, other than Washington, at which its manufacturing is carried on and from which its merchandise is distributed interstate through several sales units or branches located outside the State of Washington.

Appellant has no office in Washington and makes no contracts either for sale or purchase of merchandise there. It maintains no stock of merchandise in that state and makes there no deliveries of goods in intrastate commerce. During the years from 1937 to 1940, now in question, appellant employed eleven to thirteen salesmen under direct supervision and control of sales managers located in St. Louis. These salesmen resided in Washington; their principal activities were confined to that state; and they were compensated by commissions based upon the amount of their sales. The commissions for each year totaled more than $31,000. Appellant supplies its salesmen with a line of samples, each consisting of one shoe of a pair, which they display to prospective purchasers. On occasion they rent permanent sample rooms, for exhibiting samples, in business buildings, or rent rooms in hotels or business buildings temporarily for that purpose. The cost of such rentals is reimbursed by appellant.

The authority of the salesmen is limited to exhibiting their samples

and soliciting orders from prospective buyers, at prices and on terms

fixed by appellant. The salesmen transmit the orders to appellant’s

office in St. Louis for acceptance or rejection, and when accepted the

merchandise for filling the orders is shipped f.o.b.F.O.B. (“free on board”) is a commercial law term

indicating the point at which responsibility for goods shifts from the

seller to the buyer. In this case, International Shoe shipped its shoes

“F.O.B. Origin”, meaning it was no longer responsible for the shoes once

they left the point of shipment outside Washington. The company relied

on this legal formality to contend it engaged in no activity within

Washington.

from points outside Washington to the purchasers within

the state. All the merchandise shipped into Washington is invoiced at

the place of shipment from which collections are made. No salesman has

authority to enter into contracts or to make collections.

Historically the jurisdiction of courts to render judgment in personam is grounded on their de facto power over the defendant’s person. Hence his presence within the territorial jurisdiction of a court was prerequisite to its rendition of a judgment personally binding him. Pennoyer v. Neff, 95 U.S. 714, 733. But due process requires only that in order to subject a defendant to a judgment in personam, if he be not present within the territory of the forum, he have certain minimum contacts with it such that the maintenance of the suit does not offend “traditional notions of fair play and substantial justice.”

Since the corporate personality is a fiction, although a fiction intended to be acted upon as though it were a fact, it is clear that unlike an individual its “presence” without, as well as within, the state of its origin can be manifested only by activities carried on in its behalf by those who are authorized to act for it. To say that the corporation is so far “present” there as to satisfy due process requirements, for purposes of taxation or the maintenance of suits against it in the courts of the state, is to beg the question to be decided. For the terms “present” or “presence” are used merely to symbolize those activities of the corporation’s agent within the state which courts will deem to be sufficient to satisfy the demands of due process. Those demands may be met by such contacts of the corporation with the state of the forum as make it reasonable, in the context of our federal system of government, to require the corporation to defend the particular suit which is brought there. An “estimate of the inconveniences” which would result to the corporation from a trial away from its “home” or principal place of business is relevant in this connection.

“Presence” in the state in this sense has never been doubted when the activities of the corporation there have not only been continuous and systematic, but also give rise to the liabilities sued on, even though no consent to be sued or authorization to an agent to accept service of process has been given. Conversely it has been generally recognized that the casual presence of the corporate agent or even his conduct of single or isolated items of activities in a state in the corporation’s behalf are not enough to subject it to suit on causes of action unconnected with the activities there. To require the corporation in such circumstances to defend the suit away from its home or other jurisdiction where it carries on more substantial activities has been thought to lay too great and unreasonable a burden on the corporation to comport with due process.

While it has been held, in cases on which appellant relies, that continuous activity of some sorts within a state is not enough to support the demand that the corporation be amenable to suits unrelated to that activity, there have been instances in which the continuous corporate operations within a state were thought so substantial and of such a nature as to justify suit against it on causes of action arising from dealings entirely distinct from those activities.

Finally, although the commission of some single or occasional acts of the corporate agent in a state sufficient to impose an obligation or liability on the corporation has not been thought to confer upon the state authority to enforce it, other such acts, because of their nature and quality and the circumstances of their commission, may be deemed sufficient to render the corporation liable to suit. True, some of the decisions holding the corporation amenable to suit have been supported by resort to the legal fiction that it has given its consent to service and suit, consent being implied from its presence in the state through the acts of its authorized agents. But more realistically it may be said that those authorized acts were of such a nature as to justify the fiction.

It is evident that the criteria by which we mark the boundary line between those activities which justify the subjection of a corporation to suit, and those which do not, cannot be simply mechanical or quantitative. The test is not merely, as has sometimes been suggested, whether the activity, which the corporation has seen fit to procure through its agents in another state, is a little more or a little less. Whether due process is satisfied must depend rather upon the quality and nature of the activity in relation to the fair and orderly administration of the laws which it was the purpose of the due process clause to insure. That clause does not contemplate that a state may make binding a judgment in personam against an individual or corporate defendant with which the state has no contacts, ties, or relations. Cf. Pennoyer v. Neff.

But to the extent that a corporation exercises the privilege of conducting activities within a state, it enjoys the benefits and protection of the laws of that state. The exercise of that privilege may give rise to obligations, and, so far as those obligations arise out of or are connected with the activities within the state, a procedure which requires the corporation to respond to a suit brought to enforce them can, in most instances, hardly be said to be undue.

Applying these standards, the activities carried on in behalf of appellant in the State of Washington were neither irregular nor casual. They were systematic and continuous throughout the years in question. They resulted in a large volume of interstate business, in the course of which appellant received the benefits and protection of the laws of the state, including the right to resort to the courts for the enforcement of its rights. The obligation which is here sued upon arose out of those very activities. It is evident that these operations establish sufficient contacts or ties with the state of the forum to make it reasonable and just, according to our traditional conception of fair play and substantial justice, to permit the state to enforce the obligations which appellant has incurred there. Hence we cannot say that the maintenance of the present suit in the State of Washington involves an unreasonable or undue procedure.

We are likewise unable to conclude that the service of the process within the state upon an agent whose activities establish appellant’s “presence” there was not sufficient notice of the suit, or that the suit was so unrelated to those activities as to make the agent an inappropriate vehicle for communicating the notice. It is enough that appellant has established such contacts with the state that the particular form of substituted service adopted there gives reasonable assurance that the notice will be actual. Nor can we say that the mailing of the notice of suit to appellant by registered mail at its home office was not reasonably calculated to apprise appellant of the suit.

Appellant having rendered itself amenable to suit upon obligations arising out of the activities of its salesmen in Washington, the state may maintain the present suit in personam to collect the tax laid upon the exercise of the privilege of employing appellant’s salesmen within the state. For Washington has made one of those activities, which taken together establish appellant’s “presence” there for purposes of suit, the taxable event by which the state brings appellant within the reach of its taxing power. The state thus has constitutional power to lay the tax and to subject appellant to a suit to recover it. The activities which establish its “presence” subject it alike to taxation by the state and to suit to recover the tax.

Note: International Shoe, the FRCP, & Service of Process

International Shoe extended the reach of personal jurisdiction over out-of-state parties. As a result, the exercise of jurisdiction no longer requires personal service on the defendant while they are present in the state.

Service of the complaint and summons is still required to satisfy the notice aspect of due process. However, the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure (adopted in 1938) relaxed that requirement, permitting service by various alternate means and giving defendants an incentive to waive formal service if they receive actual notice. Fed.R.Civ.P. Rule 4.

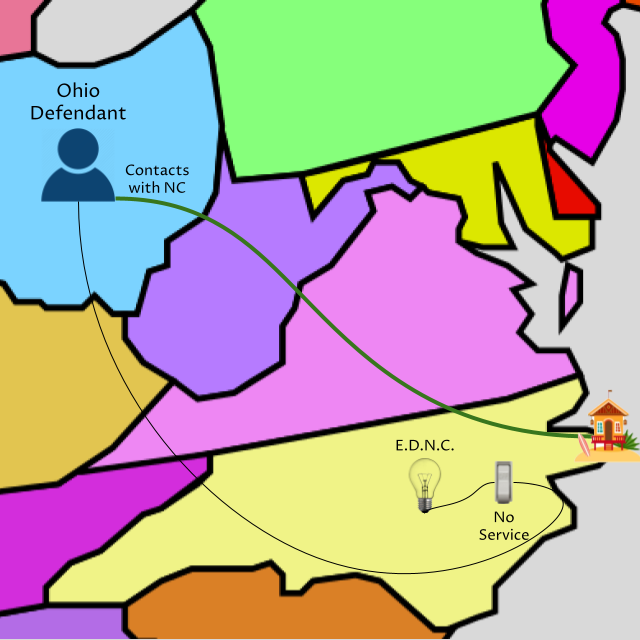

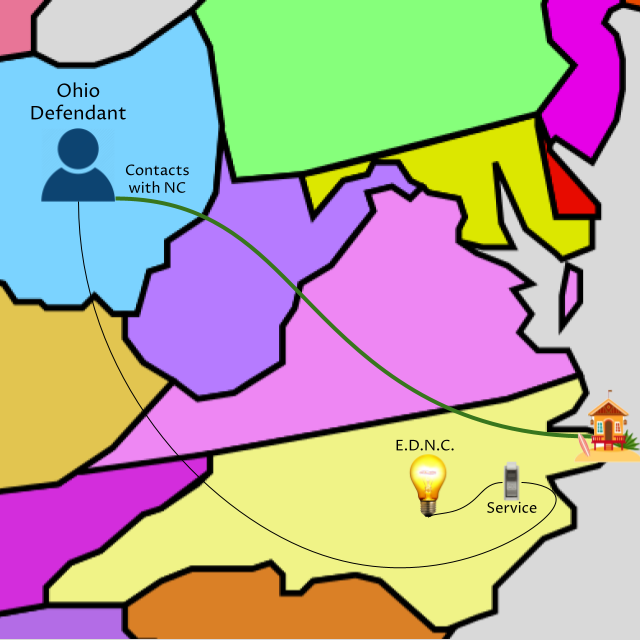

The requirements of personal jurisdiction and service of process are analogous to an electrical circuit. Minimum contacts between the defendant and the forum state are the wiring. Service of process is the switch. The court cannot exercise power over the defendant unless the wiring is connected (personal jurisdiction) and the switch is turned on (service of process).

Suppose that Dan, who lives in Ohio, rents a beach house in the Outer Banks from Pat, who lives in North Carolina. One evening, while enjoying several cocktails on the deck, Dan carelessly knocks over a Tiki torch, setting fire to the house. After Dan returns home to Ohio, Pat files suit in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of North Carolina.

The suit arises out of Dan’s conduct in North Carolina, satisfying the minimum contacts requirement for personal jurisdiction. But there has been no service of process, so the court’s power is not yet activated (Fig. 4.1).

After filing the suit, Pat serves Dan with a copy of the summons and complaint, in a manner authorized, and within the time allowed, under Rule 4. The court’s power is now active (Fig. 4.2).

Suppose instead that Pat travels from North Carolina to Ohio for a football game between the Carolina Panthers and the Cleveland Browns. Dan, a diehard Browns fan, was sitting behind Pat. Throughout the game, Pat vociferously cheers for the visiting team and mercilessly heckles the Cleveland quarterback. Annoyed with Pat’s taunts, Dan pours a large cup of beer over Pat’s head, provoking a brawl in which Pat is badly injured. After returning home, having vowed never to return to Ohio again, Pat sues Dan for battery, filing the case in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of North Carolina.

In this case, there has been service of process, but the suit does not arise out of any contacts between Dan and North Carolina. So the switch is not connected and the court has no power at all (Fig. 4.3).

Specific Jurisdiction

McGee v. International Life Ins. Co., 355 US 220 (1957)

Opinion of the Court by Justice BLACK, announced by Justice DOUGLAS.

Petitioner, Lulu B. McGee, recovered a judgment in a California state court against respondent, International Life Insurance Company, on a contract of insurance. Respondent was not served with process in California but by registered mail at its principal place of business in Texas. The California court based its jurisdiction on a state statute which subjects foreign corporations to suit in California on insurance contracts with residents of that State even though such corporations cannot be served with process within its borders.

Unable to collect the judgment in California petitioner went to Texas where she filed suit on the judgment in a Texas court. But the Texas courts refused to enforce her judgment holding it was void under the Fourteenth Amendment because service of process outside California could not give the courts of that State jurisdiction over respondent. Since the case raised important questions, not only to California but to other States which have similar laws, we granted certiorari. It is not controverted that if the California court properly exercised jurisdiction over respondent the Texas courts erred in refusing to give its judgment full faith and credit.

The material facts are relatively simple. In 1944, Lowell Franklin, a resident of California, purchased a life insurance policy from the Empire Mutual Insurance Company, an Arizona corporation. In 1948 the respondent agreed with Empire Mutual to assume its insurance obligations. Respondent then mailed a reinsurance certificate to Franklin in California offering to insure him in accordance with the terms of the policy he held with Empire Mutual. He accepted this offer and from that time until his death in 1950 paid premiums by mail from his California home to respondent’s Texas office. Petitioner, Franklin’s mother, was the beneficiary under the policy. She sent proofs of his death to the respondent but it refused to pay claiming that he had committed suicide. It appears that neither Empire Mutual nor respondent has ever had any office or agent in California. And so far as the record before us shows, respondent has never solicited or done any insurance business in California apart from the policy involved here.

Since Pennoyer v. Neff, this Court has held that the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment places some limit on the power of state courts to enter binding judgments against persons not served with process within their boundaries. But just where this line of limitation falls has been the subject of prolific controversy, particularly with respect to foreign corporations. In a continuing process of evolution this Court accepted and then abandoned “consent,” “doing business,” and “presence” as the standard for measuring the extent of state judicial power over such corporations. More recently in International Shoe Co. v. Washington, the Court decided that “due process requires only that in order to subject a defendant to a judgment in personam, if he be not present within the territory of the forum, he have certain minimum contacts with it such that the maintenance of the suit does not offend ‘traditional notions of fair play and substantial justice.’”

Looking back over this long history of litigation a trend is clearly discernible toward expanding the permissible scope of state jurisdiction over foreign corporations and other nonresidents. In part this is attributable to the fundamental transformation of our national economy over the years. Today many commercial transactions touch two or more States and may involve parties separated by the full continent. With this increasing nationalization of commerce has come a great increase in the amount of business conducted by mail across state lines. At the same time modern transportation and communication have made it much less burdensome for a party sued to defend himself in a State where he engages in economic activity.

Turning to this case we think it apparent that the Due Process Clause did not preclude the California court from entering a judgment binding on respondent. It is sufficient for purposes of due process that the suit was based on a contract which had substantial connection with that State. The contract was delivered in California, the premiums were mailed from there and the insured was a resident of that State when he died. It cannot be denied that California has a manifest interest in providing effective means of redress for its residents when their insurers refuse to pay claims. These residents would be at a severe disadvantage if they were forced to follow the insurance company to a distant State in order to hold it legally accountable. When claims were small or moderate individual claimants frequently could not afford the cost of bringing an action in a foreign forum— thus in effect making the company judgment proof. Often the crucial witnesses—as here on the company’s defense of suicide—will be found in the insured’s locality. Of course there may be inconvenience to the insurer if it is held amenable to suit in California where it had this contract but certainly nothing which amounts to a denial of due process. There is no contention that respondent did not have adequate notice of the suit or sufficient time to prepare its defenses and appear.

The California statute became law in 1949, after respondent had entered into the agreement with Franklin to assume Empire Mutual’s obligation to him. Respondent contends that application of the statute to this existing contract improperly impairs the obligation of the contract. We believe that contention is devoid of merit. The statute was remedial, in the purest sense of that term, and neither enlarged nor impaired respondent’s substantive rights or obligations under the contract. It did nothing more than to provide petitioner with a California forum to enforce whatever substantive rights she might have against respondent. At the same time respondent was given a reasonable time to appear and defend on the merits after being notified of the suit. Under such circumstances it had no vested right not to be sued in California.

The judgment is reversed and the cause is remanded to the Court of Civil Appeals of the State of Texas, First Supreme Judicial District, for further proceedings not inconsistent with this opinion.

World-Wide Volkswagen Corp. v. Woodson, 444 US 286 (1980)

Justice WHITE delivered the opinion of the Court.

The issue before us is whether, consistently with the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, an Oklahoma court may exercise in personam jurisdiction over a nonresident automobile retailer and its wholesale distributor in a products-liability action, when the defendants’ only connection with Oklahoma is the fact that an automobile sold in New York to New York residents became involved in an accident in Oklahoma.

I

Respondents Harry and Kay Robinson purchased a new Audi automobile from petitioner Seaway Volkswagen, Inc. (Seaway), in Massena, N. Y., in 1976. The following year the Robinson family, who resided in New York, left that State for a new home in Arizona. As they passed through the State of Oklahoma, another car struck their Audi in the rear, causing a fire which severely burned Kay Robinson and her two children.

The Robinsons subsequently brought a products-liability action in the District Court for Creek County, Okla., claiming that their injuries resulted from defective design and placement of the Audi’s gas tank and fuel system. They joined as defendants the automobile’s manufacturer, Audi NSU Auto Union Aktiengesellschaft (Audi); its importer, Volkswagen of America, Inc. (Volkswagen); its regional distributor, petitioner World-Wide Volkswagen Corp. (World-Wide); and its retail dealer, petitioner Seaway. Seaway and World-Wide entered special appearances, claiming that Oklahoma’s exercise of jurisdiction over them would offend the limitations on the State’s jurisdiction imposed by the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The facts presented to the District Court showed that World-Wide is incorporated and has its business office in New York. It distributes vehicles, parts, and accessories, under contract with Volkswagen, to retail dealers in New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut. Seaway, one of these retail dealers, is incorporated and has its place of business in New York. Insofar as the record reveals, Seaway and World-Wide are fully independent corporations whose relations with each other and with Volkswagen and Audi are contractual only. Respondents adduced no evidence that either World-Wide or Seaway does any business in Oklahoma, ships or sells any products to or in that State, has an agent to receive process there, or purchases advertisements in any media calculated to reach Oklahoma. In fact, as respondents’ counsel conceded at oral argument, there was no showing that any automobile sold by World-Wide or Seaway has ever entered Oklahoma with the single exception of the vehicle involved in the present case.

II

The Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment limits the power of a state court to render a valid personal judgment against a nonresident defendant. A judgment rendered in violation of due process is void in the rendering State and is not entitled to full faith and credit elsewhere. Due process requires that the defendant be given adequate notice of the suit, and be subject to the personal jurisdiction of the court, In the present case, the only question is whether these particular petitioners were subject to the jurisdiction of the Oklahoma courts.

As has long been settled, and as we reaffirm today, a state court may exercise personal jurisdiction over a nonresident defendant only so long as there exist “minimum contacts” between the defendant and the forum State. International Shoe Co. v. Washington. The concept of minimum contacts, in turn, can be seen to perform two related, but distinguishable, functions. It protects the defendant against the burdens of litigating in a distant or inconvenient forum. And it acts to ensure that the States, through their courts, do not reach out beyond the limits imposed on them by their status as coequal sovereigns in a federal system.

The protection against inconvenient litigation is typically described in terms of “reasonableness” or “fairness.” We have said that the defendant’s contacts with the forum State must be such that maintenance of the suit “does not offend ‘traditional notions of fair play and substantial justice.’” International Shoe Co. The relationship between the defendant and the forum must be such that it is “reasonable to require the corporation to defend the particular suit which is brought there.” Implicit in this emphasis on reasonableness is the understanding that the burden on the defendant, while always a primary concern, will in an appropriate case be considered in light of other relevant factors, including the forum State’s interest in adjudicating the dispute, the plaintiff’s interest in obtaining convenient and effective relief, at least when that interest is not adequately protected by the plaintiff’s power to choose the forum, the interstate judicial system’s interest in obtaining the most efficient resolution of controversies; and the shared interest of the several States in furthering fundamental substantive social policies.

The limits imposed on state jurisdiction by the Due Process Clause, in its role as a guarantor against inconvenient litigation, have been substantially relaxed over the years. As we noted in McGee v. International Life Ins. Co., this trend is largely attributable to a fundamental transformation in the American economy:

Today many commercial transactions touch two or more States and may involve parties separated by the full continent. With this increasing nationalization of commerce has come a great increase in the amount of business conducted by mail across state lines. At the same time modern transportation and communication have made it much less burdensome for a party sued to defend himself in a State where he engages in economic activity.

The historical developments noted in McGee, of course, have only accelerated in the generation since that case was decided.

Nevertheless, we have never accepted the proposition that state lines are irrelevant for jurisdictional purposes, nor could we, and remain faithful to the principles of interstate federalism embodied in the Constitution. The economic interdependence of the States was foreseen and desired by the Framers. In the Commerce Clause, they provided that the Nation was to be a common market, a “free trade unit” in which the States are debarred from acting as separable economic entities. But the Framers also intended that the States retain many essential attributes of sovereignty, including, in particular, the sovereign power to try causes in their courts. The sovereignty of each State, in turn, implied a limitation on the sovereignty of all of its sister States—a limitation express or implicit in both the original scheme of the Constitution and the Fourteenth Amendment.

Hence, even while abandoning the shibboleth that “the authority of every tribunal is necessarily restricted by the territorial limits of the State in which it is established,” Pennoyer v. Neff, we emphasized that the reasonableness of asserting jurisdiction over the defendant must be assessed “in the context of our federal system of government,” International Shoe Co. v. Washington, and stressed that the Due Process Clause ensures not only fairness, but also the “orderly administration of the laws,” id. As we noted in Hanson v. Denckla, 357 U. S. 235, 250-251 (1958):

As technological progress has increased the flow of commerce between the States, the need for jurisdiction over nonresidents has undergone a similar increase. At the same time, progress in communications and transportation has made the defense of a suit in a foreign tribunal less burdensome. In response to these changes, the requirements for personal jurisdiction over nonresidents have evolved from the rigid rule of Pennoyer v. Neff to the flexible standard of International Shoe Co. v. Washington. But it is a mistake to assume that this trend heralds the eventual demise of all restrictions on the personal jurisdiction of state courts. Those restrictions are more than a guarantee of immunity from inconvenient or distant litigation. They are a consequence of territorial limitations on the power of the respective States.

Thus, the Due Process Clause “does not contemplate that a state may make binding a judgment in personam against an individual or corporate defendant with which the state has no contacts, ties, or relations.” International Shoe Co. Even if the defendant would suffer minimal or no inconvenience from being forced to litigate before the tribunals of another State; even if the forum State has a strong interest in applying its law to the controversy; even if the forum State is the most convenient location for litigation, the Due Process Clause, acting as an instrument of interstate federalism, may sometimes act to divest the State of its power to render a valid judgment.

III

Applying these principles to the case at hand, we find in the record before us a total absence of those affiliating circumstances that are a necessary predicate to any exercise of state-court jurisdiction. Petitioners carry on no activity whatsoever in Oklahoma. They close no sales and perform no services there. They avail themselves of none of the privileges and benefits of Oklahoma law. They solicit no business there either through salespersons or through advertising reasonably calculated to reach the State. Nor does the record show that they regularly sell cars at wholesale or retail to Oklahoma customers or residents or that they indirectly, through others, serve or seek to serve the Oklahoma market. In short, respondents seek to base jurisdiction on one, isolated occurrence and whatever inferences can be drawn therefrom: the fortuitous circumstance that a single Audi automobile, sold in New York to New York residents, happened to suffer an accident while passing through Oklahoma.

It is argued, however, that because an automobile is mobile by its very design and purpose it was “foreseeable” that the Robinsons’ Audi would cause injury in Oklahoma. Yet “foreseeability” alone has never been a sufficient benchmark for personal jurisdiction under the Due Process Clause.

This is not to say, of course, that foreseeability is wholly irrelevant. But the foreseeability that is critical to due process analysis is not the mere likelihood that a product will find its way into the forum State. Rather, it is that the defendant’s conduct and connection with the forum State are such that he should reasonably anticipate being haled into court there. The Due Process Clause, by ensuring the “orderly administration of the laws,” International Shoe Co., gives a degree of predictability to the legal system that allows potential defendants to structure their primary conduct with some minimum assurance as to where that conduct will and will not render them liable to suit.

When a corporation “purposefully avails itself of the privilege of conducting activities within the forum State,” Hanson v. Denckla, it has clear notice that it is subject to suit there, and can act to alleviate the risk of burdensome litigation by procuring insurance, passing the expected costs on to customers, or, if the risks are too great, severing its connection with the State. Hence if the sale of a product of a manufacturer or distributor such as Audi or Volkswagen is not simply an isolated occurrence, but arises from the efforts of the manufacturer or distributor to serve, directly or indirectly, the market for its product in other States, it is not unreasonable to subject it to suit in one of those States if its allegedly defective merchandise has there been the source of injury to its owner or to others. The forum State does not exceed its powers under the Due Process Clause if it asserts personal jurisdiction over a corporation that delivers its products into the stream of commerce with the expectation that they will be purchased by consumers in the forum State.

But there is no such or similar basis for Oklahoma jurisdiction over World-Wide or Seaway in this case. Seaway’s sales are made in Massena, N. Y. World-Wide’s market, although substantially larger, is limited to dealers in New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut. There is no evidence of record that any automobiles distributed by World-Wide are sold to retail customers outside this tristate area. It is foreseeable that the purchasers of automobiles sold by World-Wide and Seaway may take them to Oklahoma. But the mere “unilateral activity of those who claim some relationship with a nonresident defendant cannot satisfy the requirement of contact with the forum State.” Hanson v. Denckla.

In a variant on the previous argument, it is contended that jurisdiction can be supported by the fact that petitioners earn substantial revenue from goods used in Oklahoma. While this inference seems less than compelling on the facts of the instant case, we need not question the court’s factual findings in order to reject its reasoning.

This argument seems to make the point that the purchase of automobiles in New York, from which the petitioners earn substantial revenue, would not occur but for the fact that the automobiles are capable of use in distant States like Oklahoma. Respondents observe that the very purpose of an automobile is to travel, and that travel of automobiles sold by petitioners is facilitated by an extensive chain of Volkswagen service centers throughout the country, including some in Oklahoma. However, financial benefits accruing to the defendant from a collateral relation to the forum State will not support jurisdiction if they do not stem from a constitutionally cognizable contact with that State. In our view, whatever marginal revenues petitioners may receive by virtue of the fact that their products are capable of use in Oklahoma is far too attenuated a contact to justify that State’s exercise of in personam jurisdiction over them.

Justice BRENNAN, dissenting.

The Court holds that the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment bars the States from asserting jurisdiction over the defendants in these two cases. In each case the Court so decides because it fails to find the “minimum contacts” that have been required since International Shoe Co. v. Washington. Because I believe that the Court reads International Shoe and its progeny too narrowly, and because I believe that the standards enunciated by those cases may already be obsolete as constitutional boundaries, I dissent.

I

The Court’s opinions focus tightly on the existence of contacts between the forum and the defendant. In so doing, they accord too little weight to the strength of the forum State’s interest in the case and fail to explore whether there would be any actual inconvenience to the defendant. The essential inquiry in locating the constitutional limits on state-court jurisdiction over absent defendants is whether the particular exercise of jurisdiction offends “‘traditional notions of fair play and substantial justice.’” International Shoe. The clear focus in International Shoe was on fairness and reasonableness. The Court specifically declined to establish a mechanical test based on the quantum of contacts between a State and the defendant:

Whether due process is satisfied must depend rather upon the quality and nature of the activity in relation to the fair and orderly administration of the laws which it was the purpose of the due process clause to insure. That clause does not contemplate that a state may make binding a judgment in personam against an individual or corporate defendant with which the state has no contacts, ties, or relations.

The existence of contacts, so long as there were some, was merely one way of giving content to the determination of fairness and reasonableness.

Surely International Shoe contemplated that the significance of the contacts necessary to support jurisdiction would diminish if some other consideration helped establish that jurisdiction would be fair and reasonable. The interests of the State and other parties in proceeding with the case in a particular forum are such considerations. McGee v. International Life Ins. Co., 355 U. S. 220, 223 (1957), for instance, accorded great importance to a State’s “manifest interest in providing effective means of redress” for its citizens.

Another consideration is the actual burden a defendant must bear in defending the suit in the forum. Because lesser burdens reduce the unfairness to the defendant, jurisdiction may be justified despite less significant contacts. The burden, of course, must be of constitutional dimension. Due process limits on jurisdiction do not protect a defendant from all inconvenience of travel, and it would not be sensible to make the constitutional rule turn solely on the number of miles the defendant must travel to the courtroom. Instead, the constitutionally significant “burden” to be analyzed relates to the mobility of the defendant’s defense. For instance, if having to travel to a foreign forum would hamper the defense because witnesses or evidence or the defendant himself were immobile, or if there were a disproportionately large number of witnesses or amount of evidence that would have to be transported at the defendant’s expense, or if being away from home for the duration of the trial would work some special hardship on the defendant, then the Constitution would require special consideration for the defendant’s interests.

That considerations other than contacts between the forum and the defendant are relevant necessarily means that the Constitution does not require that trial be held in the State which has the “best contacts” with the defendant.The defendant has no constitutional entitlement to the best forum or, for that matter, to any particular forum. We need only determine whether the forum States in these cases satisfy the constitutional minimum.

II

I would find that the forum State has an interest in permitting the litigation to go forward, the litigation is connected to the forum, the defendant is linked to the forum, and the burden of defending is not unreasonable. Accordingly, I would hold that it is neither unfair nor unreasonable to require these defendants to defend in the forum State.

B

The interest of the forum State and its connection to the litigation is strong. The automobile accident underlying the litigation occurred in Oklahoma. The plaintiffs were hospitalized in Oklahoma when they brought suit. Essential witnesses and evidence were in Oklahoma. The State has a legitimate interest in enforcing its laws designed to keep its highway system safe, and the trial can proceed at least as efficiently in Oklahoma as anywhere else.

The petitioners are not unconnected with the forum. Although both sell automobiles within limited sales territories, each sold the automobile which in fact was driven to Oklahoma where it was involved in an accident. It may be true, as the Court suggests, that each sincerely intended to limit its commercial impact to the limited territory, and that each intended to accept the benefits and protection of the laws only of those States within the territory. But obviously these were unrealistic hopes that cannot be treated as an automatic constitutional shield.

An automobile simply is not a stationary item or one designed to be used in one place. An automobile is intended to be moved around. Someone in the business of selling large numbers of automobiles can hardly plead ignorance of their mobility or pretend that the automobiles stay put after they are sold. It is not merely that a dealer in automobiles foresees that they will move. The dealer actually intends that the purchasers will use the automobiles to travel to distant States where the dealer does not directly “do business.” The sale of an automobile does purposefully inject the vehicle into the stream of interstate commerce so that it can travel to distant States.

Furthermore, an automobile seller derives substantial benefits from States other than its own. A large part of the value of automobiles is the extensive, nationwide network of highways. Significant portions of that network have been constructed by and are maintained by the individual States, including Oklahoma. The States, through their highway programs, contribute in a very direct and important way to the value of petitioners’ businesses. Additionally, a network of other related dealerships with their service departments operates throughout the country under the protection of the laws of the various States, including Oklahoma, and enhances the value of petitioners’ businesses by facilitating their customers’ traveling.

Thus, the Court errs in its conclusion that “petitioners have no contacts, ties, or relations’” with Oklahoma. There obviously are contacts, and, given Oklahoma’s connection to the litigation, the contacts are sufficiently significant to make it fair and reasonable for the petitioners to submit to Oklahoma’s jurisdiction.

III

International Shoe inherited its defendant focus from Pennoyer v. Neff, and represented the last major step this Court has taken in the long process of liberalizing the doctrine of personal jurisdiction. Though its flexible approach represented a major advance, the structure of our society has changed in many significant ways since International Shoe was decided in 1945. Mr. Justice Black, writing for the Court in McGee v. International Life Ins. Co., recognized that “a trend is clearly discernible toward expanding the permissible scope of state jurisdiction over foreign corporations and other nonresidents.” He explained the trend as follows:

In part this is attributable to the fundamental transformation of our national economy over the years. Today many commercial transactions touch two or more States and may involve parties separated by the full continent. With this increasing nationalization of commerce has come a great increase in the amount of business conducted by mail across state lines. At the same time modern transportation and communication have made it much less burdensome for a party sued to defend himself in a State where he engages in economic activity.

Both the nationalization of commerce and the ease of transportation and communication have accelerated in the generation since 1957. The model of society on which the International Shoe Court based its opinion is no longer accurate. Business people, no matter how local their businesses, cannot assume that goods remain in the business’ locality. Customers and goods can be anywhere else in the country usually in a matter of hours and always in a matter of a very few days.

In answering the question whether or not it is fair and reasonable to allow a particular forum to hold a trial binding on a particular defendant, the interests of the forum State and other parties loom large in today’s world and surely are entitled to as much weight as are the interests of the defendant. The “orderly administration of the laws” provides a firm basis for according some protection to the interests of plaintiffs and States as well as of defendants. Certainly, I cannot see how a defendant’s right to due process is violated if the defendant suffers no inconvenience.

The conclusion I draw is that constitutional concepts of fairness no longer require the extreme concern for defendants that was once necessary. Rather, minimum contacts must exist “among the parties, the contested transaction, and the forum State.” The contacts between any two of these should not be determinate.

Justice BLACKMUN, dissenting.

I confess that I am somewhat puzzled why the plaintiffs in this litigation are so insistent that the regional distributor and the retail dealer, the petitioners here, who handled the ill-fated Audi automobile involved in this litigation, be named defendants. It would appear that the manufacturer and the importer, whose subjectability to Oklahoma jurisdiction is not challenged before this Court, ought not to be judgment-proof. It may, of course, ultimately amount to a contest between insurance companies that, once begun, is not easily brought to a termination. Having made this much of an observation, I pursue it no further.

Ford Motor Co. v. Mont. Eighth Judicial Dist. Ct., 141 S.Ct. 1017 (2021)

Justice KAGAN delivered the opinion of the Court.

In each of these two cases, a state court held that it had jurisdiction over Ford Motor Company in a products-liability suit stemming from a car accident. The accident happened in the State where suit was brought. The victim was one of the State’s residents. And Ford did substantial business in the State—among other things, advertising, selling, and servicing the model of vehicle the suit claims is defective. Still, Ford contends that jurisdiction is improper because the particular car involved in the crash was not first sold in the forum State, nor was it designed or manufactured there. We reject that argument. When a company like Ford serves a market for a product in a State and that product causes injury in the State to one of its residents, the State’s courts may entertain the resulting suit.

I

Ford is a global auto company. It is incorporated in Delaware and headquartered in Michigan. But its business is everywhere. Ford markets, sells, and services its products across the United States and overseas. In this country alone, the company annually distributes over 2.5 million new cars, trucks, and SUVs to over 3,200 licensed dealerships. Ford also encourages a resale market for its products: Almost all its dealerships buy and sell used Fords, as well as selling new ones. To enhance its brand and increase its sales, Ford engages in wide-ranging promotional activities, including television, print, online, and direct-mail advertisements. No matter where you live, you’ve seen them: “Have you driven a Ford lately?” or “Built Ford Tough.” Ford also ensures that consumers can keep their vehicles running long past the date of sale. The company provides original parts to auto supply stores and repair shops across the country. (Goes another slogan: “Keep your Ford a Ford.”) And Ford’s own network of dealers offers an array of maintenance and repair services, thus fostering an ongoing relationship between Ford and its customers.

Accidents involving two of Ford’s vehicles—a 1996 Explorer and a 1994 Crown Victoria—are at the heart of the suits before us. One case comes from Montana. Markkaya Gullett was driving her Explorer near her home in the State when the tread separated from a rear tire. The vehicle spun out, rolled into a ditch, and came to rest upside down. Gullett died at the scene of the crash. The representative of her estate sued Ford in Montana state court, bringing claims for a design defect, failure to warn, and negligence. The second case comes from Minnesota. Adam Bandemer was a passenger in his friend’s Crown Victoria, traveling on a rural road in the State to a favorite ice-fishing spot. When his friend rear-ended a snowplow, this car too landed in a ditch. Bandemer’s air bag failed to deploy, and he suffered serious brain damage. He sued Ford in Minnesota state court, asserting products-liability, negligence, and breach-of-warranty claims.

Ford moved to dismiss the two suits for lack of personal jurisdiction, on basically identical grounds. According to Ford, the state court (whether in Montana or Minnesota) had jurisdiction only if the company’s conduct in the State had given rise to the plaintiff’s claims. And that causal link existed, Ford continued, only if the company had designed, manufactured, or—most likely—sold in the State the particular vehicle involved in the accident. In neither suit could the plaintiff make that showing. Ford had designed the Explorer and Crown Victoria in Michigan, and it had manufactured the cars in (respectively) Kentucky and Canada. Still more, the company had originally sold the cars at issue outside the forum States—the Explorer in Washington, the Crown Victoria in North Dakota. Only later resales and relocations by consumers had brought the vehicles to Montana and Minnesota. That meant, in Ford’s view, that the courts of those States could not decide the suits.

Both the Montana and the Minnesota Supreme Courts (affirming lower court decisions) rejected Ford’s argument.

We granted certiorari to consider if Ford is subject to jurisdiction in these cases. We hold that it is.

II

A

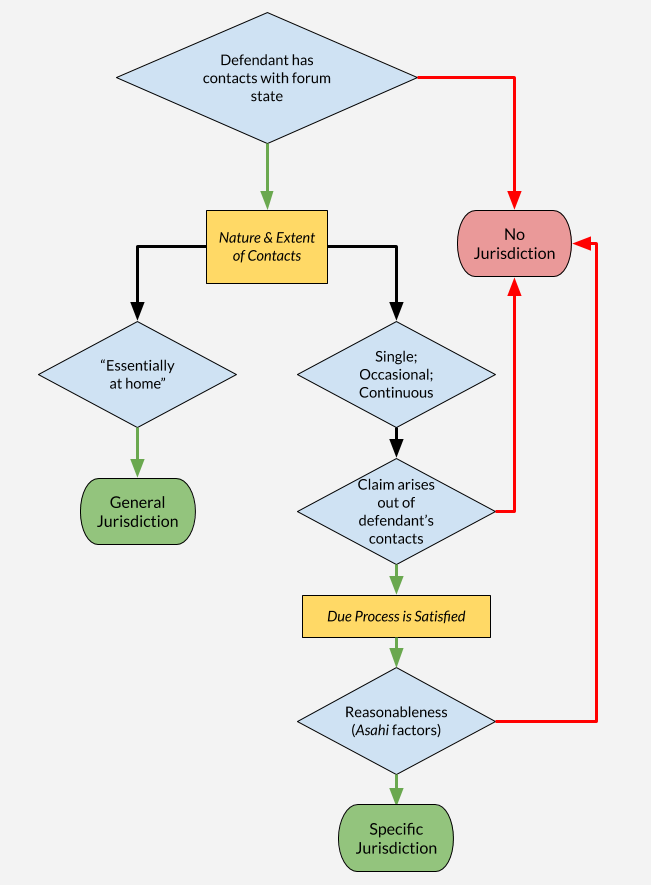

The Fourteenth Amendment’s Due Process Clause limits a state court’s power to exercise jurisdiction over a defendant. The canonical decision in this area remains International Shoe Co. v. Washington. There, the Court held that a tribunal’s authority depends on the defendant’s having such “contacts” with the forum State that “the maintenance of the suit” is “reasonable, in the context of our federal system of government,” and “does not offend traditional notions of fair play and substantial justice.” In giving content to that formulation, the Court has long focused on the nature and extent of “the defendant’s relationship to the forum State.” That focus led to our recognizing two kinds of personal jurisdiction: general (sometimes called all-purpose) jurisdiction and specific (sometimes called case-linked) jurisdiction.

A state court may exercise general jurisdiction only when a defendant is “essentially at home” in the State. General jurisdiction, as its name implies, extends to “any and all claims” brought against a defendant. Those claims need not relate to the forum State or the defendant’s activity there; they may concern events and conduct anywhere in the world. But that breadth imposes a correlative limit: Only a select “set of affiliations with a forum” will expose a defendant to such sweeping jurisdiction. what we have called the “paradigm” case, an individual is subject to general jurisdiction in her place of domicile. And the “equivalent” forums for a corporation are its place of incorporation and principal place of business. So general jurisdiction over Ford (as all parties agree) attaches in Delaware and Michigan—not in Montana and Minnesota.

Specific jurisdiction is different: It covers defendants less intimately connected with a State, but only as to a narrower class of claims. The contacts needed for this kind of jurisdiction often go by the name “purposeful availment.” The defendant, we have said, must take “some act by which it purposefully avails itself of the privilege of conducting activities within the forum State.” The contacts must be the defendant’s own choice and not “random, isolated, or fortuitous.” They must show that the defendant deliberately “reached out beyond” its home—by, for example, “exploiting a market” in the forum State or entering a contractual relationship centered there. Yet even then—because the defendant is not “at home”—the forum State may exercise jurisdiction in only certain cases. The plaintiff’s claims, we have often stated, “must arise out of or relate to the defendant’s contacts” with the forum. Or put just a bit differently, “there must be ‘an affiliation between the forum and the underlying controversy, principally, an activity or an occurrence that takes place in the forum State and is therefore subject to the State’s regulation.’”

These rules derive from and reflect two sets of values—treating defendants fairly and protecting “interstate federalism.” Our decision in International Shoe founded specific jurisdiction on an idea of reciprocity between a defendant and a State: When (but only when) a company “exercises the privilege of conducting activities within a state”—thus “enjoying the benefits and protection of its laws”—the State may hold the company to account for related misconduct. Later decisions have added that our doctrine similarly provides defendants with “fair warning”—knowledge that “a particular activity may subject it to the jurisdiction of a foreign sovereign.” A defendant can thus “structure its primary conduct” to lessen or avoid exposure to a given State’s courts. And this Court has considered alongside defendants’ interests those of the States in relation to each other. One State’s “sovereign power to try” a suit, we have recognized, may prevent “sister States” from exercising their like authority. The law of specific jurisdiction thus seeks to ensure that States with “little legitimate interest” in a suit do not encroach on States more affected by the controversy.

B

Ford contends that our jurisdictional rules prevent Montana’s and Minnesota’s courts from deciding these two suits. In making that argument, Ford does not contest that it does substantial business in Montana and Minnesota—that it actively seeks to serve the market for automobiles and related products in those States. Or to put that concession in more doctrinal terms, Ford agrees that it has “purposefully availed itself of the privilege of conducting activities” in both places. Ford’s claim is instead that those activities do not sufficiently connect to the suits, even though the resident-plaintiffs allege that Ford cars malfunctioned in the forum States. In Ford’s view, the needed link must be causal in nature: Jurisdiction attaches “only if the defendant’s forum conduct gave rise to the plaintiff’s claims.” And that rule reduces, Ford thinks, to locating specific jurisdiction in the State where Ford sold the car in question, or else the States where Ford designed and manufactured the vehicle. On that view, the place of accident and injury is immaterial. So (Ford says) Montana’s and Minnesota’s courts have no power over these cases.

But Ford’s causation-only approach finds no support in this Court’s requirement of a “connection” between a plaintiff’s suit and a defendant’s activities. That rule indeed serves to narrow the class of claims over which a state court may exercise specific jurisdiction. But not quite so far as Ford wants. None of our precedents has suggested that only a strict causal relationship between the defendant’s in-state activity and the litigation will do. As just noted, our most common formulation of the rule demands that the suit “arise out of or relate to the defendant’s contacts with the forum.” The first half of that standard asks about causation; but the back half, after the “or,” contemplates that some relationships will support jurisdiction without a causal showing. That does not mean anything goes. In the sphere of specific jurisdiction, the phrase “relate to” incorporates real limits, as it must to adequately protect defendants foreign to a forum. But again, we have never framed the specific jurisdiction inquiry as always requiring proof of causation—i.e., proof that the plaintiff’s claim came about because of the defendant’s in-state conduct. So the case is not over even if, as Ford argues, a causal test would put jurisdiction in only the States of first sale, manufacture, and design. A different State’s courts may yet have jurisdiction, because of another “activity or occurrence” involving the defendant that takes place in the State.

And indeed, this Court has stated that specific jurisdiction attaches in cases identical to the ones here—when a company like Ford serves a market for a product in the forum State and the product malfunctions there. In World-Wide Volkswagen, the Court held that an Oklahoma court could not assert jurisdiction over a New York car dealer just because a car it sold later caught fire in Oklahoma. But in so doing, we contrasted the dealer’s position to that of two other defendants—Audi, the car’s manufacturer, and Volkswagen, the car’s nationwide importer (neither of which contested jurisdiction):

If the sale of a product of a manufacturer or distributor such as Audi or Volkswagen is not simply an isolated occurrence, but arises from the efforts of the manufacturer or distributor to serve, directly or indirectly, the market for its product in several or all other States, it is not unreasonable to subject it to suit in one of those States if its allegedly defective merchandise has there been the source of injury to its owner or to others.

Or said another way, if Audi and Volkswagen’s business deliberately extended into Oklahoma (among other States), then Oklahoma’s courts could hold the companies accountable for a car’s catching fire there—even though the vehicle had been designed and made overseas and sold in New York. For, the Court explained, a company thus “purposefully availing itself”of the Oklahoma auto market “has clear notice” of its exposure in that State to suits arising from local accidents involving its cars. And the company could do something about that exposure: It could “act to alleviate the risk of burdensome litigation by procuring insurance, passing the expected costs on to customers, or, if the risks are still too great, severing its connection with the State.”

Our conclusion in World-Wide Volkswagen—though, as Ford notes, technically “dicta”—has appeared and reappeared in many cases since. So, for example, the Court in Keeton invoked that part of World-Wide Volkswagen to show that when a corporation has “continuously and deliberately exploited a State’s market, it must reasonably anticipate being haled into that State’s courts” to defend actions “based on” products causing injury there. And in Daimler, we used the Audi/Volkswagen scenario as a paradigm case of specific jurisdiction (though now naming Daimler, the maker of Mercedes Benzes). Said the Court, to “illustrate” specific jurisdiction’s “province”: A California court would exercise specific jurisdiction “if a California plaintiff, injured in a California accident involving a Daimler-manufactured vehicle, sued Daimler in that court alleging that the vehicle was defectively designed.” As in World-Wide Volkswagen, the Court did not limit jurisdiction to where the car was designed, manufactured, or first sold. Substitute Ford for Daimler, Montana and Minnesota for California, and the Court’s “illustrative” case becomes … the two cases before us.