Choice of Governing Law

State or Federal Law in Diversity Cases

The Rules of Decision Act

28 U.S.C. § 1652

State laws as rules of decision

The laws of the several states, except where the Constitution or treaties of the United States or Acts of Congress otherwise require or provide, shall be regarded as rules of decision in civil actions in the courts of the United States, in cases where they apply.

Swift v. Tyson, 41 U.S. 1 (1842)

Summary of Facts

The defendant, George TysenThe spelling of Tysen’s name in the Supreme Court’s

opinion appears to have been an error. See Alfred B. Teton, The

Story of Swift v. Tyson, 35 Illinois Law Review 519, 530 n.59

(1940).

purchased some land from Nathaniel Norton and Jairus

Keith. As partial payment, Tyson gave Norton and Keith a bill of

exchange.“A bill of exchange, a short-term negotiable

instrument, is a signed, unconditional, written order binding one party

to pay a fixed sum of money to another party on demand or at a

predetermined date.” Wex Legal

Dictionary

It turned out that, not only was the land virtually

worthless, North and Keith did not actually own it. Before the bill of

exchange came due, Norton signed it over to the plaintiff, John Swift,

ostensibly in payment of a debt.Swift may have been in cahoots with Norton and Keith:

“The circumstances surrounding the giving of the promissory note of

Norton and Keith to Swift and the fact that after indorsing the bill to

Swift the two erstwhile real estate salesmen disappeared, all hinted

that Swift, Keith, and Norton had attempted to manufacture Swift’s

status as bona fide holder in order to allow him to collect the bill in

spite of the hanky panky surrounding the land deal. Perhaps in return

Swift gave Norton and Keith enough cash with which to make their

escape.” William P. LaPiana, Swift v. Tyson and the Brooding

Omnipresence in the Sky: An Investigation of the Idea of Law in

Antebellum America, 20 Suffolk University Law Review 771, 796

(1986).

Swift then sought payment on the bill of exchange from Tyson, who refused on the ground that it was procured by fraud. Swift (a resident of Maine) sued Tyson (a resident of New York) in federal court, which had jurisdiction based on diversity of citizenship.

Justice STORY delivered the opinion of the Court.

There is no doubt, that a bonâ fide holder of a negotiable instrument for a valuable consideration, without any notice of facts which impeach its validity as between the antecedent parties, if he takes it under an endorsement made before the same becomes due, holds the title unaffected by these facts, and may recover thereon, although as between the antecedent parties the transaction may be without any legal validity. This is a doctrine so long and so well established, and so essential to the security of negotiable paper, that it is laid up among the fundamentals of the law, and requires no authority or reasoning to be now brought in its support. As little doubt is there, that the holder of any negotiable paper, before it is due, is not bound to prove that he is a bonâ fide holder for a valuable consideration, without notice; for the law will presume that, in the absence of all rebutting proofs, and therefore it is incumbent upon the defendant to establish by way of defence satisfactory proofs of the contrary, and thus to overcome the primâ facie title of the plaintiff.

In the present case, the plaintiff is a bonâ fide holder without notice for what the law deems a good and valid consideration, that is, for a pre-existing debt; and the only real question in the cause is, whether, under the circumstances of the present case, such a pre-existing debt constitutes a valuable consideration in the sense of the general rule applicable to negotiable instruments. We say, under the circumstances of the present case, for the acceptance having been made in New York, the argument on behalf of the defendant is, that the contract is to be treated as a New York contract, and therefore to be governed by the laws of New York, as expounded by its Courts, as well upon general principles, as by the express provisions of the [Rules of Decision Act]. And then it is further contended, that by the law of New York, as thus expounded by its Courts, a pre-existing debt does not constitute, in the sense of the general rule, a valuable consideration applicable to negotiable instruments.

But, admitting the doctrine to be fully settled in New York, it

remains to be considered, whether it is obligatory upon this Court, if

it differs from the principles established in the general commercial

law. It is observable that the Courts of New York do not found their

decisions upon this point upon any local statute, or positive, fixed, or

ancient local usage: but they deduce the doctrine from the general

principles of commercial law. It is, however, contended, that the [Rules

of Decision Act] furnishes a rule obligatory upon this Court to follow

the decisions of the state tribunals in all cases to which they apply.

That section provides “that the laws of the several states, except where

the Constitution, treaties, or statutes of the United States shall

otherwise require or provide, shall be regarded as rules of decision in

trials at common law in the Courts of the United States, in cases where

they apply.” In order to maintain the argument, it is essential,

therefore, to hold, that the word “laws,” in this section, includes

within the scope of its meaning the decisions of the local tribunals. In

the ordinary use of language it will hardly be contended that the

decisions of Courts constitute laws. They are, at most, only evidence of

what the laws are; and are not of themselves laws. They are often

re-examined, reversed, and qualified by the Courts themselves, whenever

they are found to be either defective, or ill-founded, or otherwise

incorrect. The laws of a state are more usually understood to mean the

rules and enactments promulgated by the legislative authority thereof,

or long established local customs having the force of laws. In all the

various cases which have hitherto come before us for decision, this

Court have uniformly supposed, that the true interpretation of the

thirty-fourth section limited its application to state laws strictly

local, that is to say, to the positive statutes of the state, and the

construction thereof adopted by the local tribunals, and to rights and

titles to things having a permanent locality, such as the rights and

titles to real estate, and other matters immovable and intraterritorial

in their nature and character. It never has been supposed by us, that

the section did apply, or was designed to apply, to questions of a more

general nature, not at all dependent upon local statutes or local usages

of a fixed and permanent operation, as, for example, to the construction

of ordinary contracts or other written instruments, and especially to

questions of general commercial law, where the state tribunals are

called upon to perform the like functions as ourselves, that is, to

ascertain upon general reasoning and legal analogies, what is the true

exposition of the contract or instrument, or what is the just rule

furnished by the principles of commercial law to govern the case. And we

have not now the slightest difficulty in holding, that this section,

upon its true intendment and construction, is strictly limited to local

statutes and local usages of the character before stated, and does not

extend to contracts and other instruments of a commercial nature, the

true interpretation and effect whereof are to be sought, not in the

decisions of the local tribunals, but in the general principles and

doctrines of commercial jurisprudence. Undoubtedly, the decisions of the

local tribunals upon such subjects are entitled to, and will receive,

the most deliberate attention and respect of this Court; but they cannot

furnish positive rules, or conclusive authority, by which our own

judgments are to be bound up and governed. The law respecting negotiable

instruments may be truly declared in the language of Cicero, to be in a

great measure, not the law of a single country only, but of the

commercial world.“There will not be different laws at Rome and at

Athens, or different laws now and in the future, but one eternal and

unchangeable law will be valid for all nations and all times”.

Non erit alia lex Romæ, alia Athenis, alia nunc, alia

posthac, sed et apud omnes gentes, et omni tempore, una eademque lex

obtenebit.

It becomes necessary for us, therefore, upon the present occasion to express our own opinion of the true result of the commercial law upon the question now before us. And we have no hesitation in saying, that a pre-existing debt does constitute a valuable consideration in the sense of the general rule already stated, as applicable to negotiable instruments. Assuming it to be true, (which, however, may well admit of some doubt from the generality of the language,) that the holder of a negotiable instrument is unaffected with the equities between the antecedent parties, of which he has no notice, only where he receives it in the usual course of trade and business for a valuable consideration, before it becomes due; we are prepared to say, that receiving it in payment of, or as security for a pre-existing debt, is according to the known usual course of trade and business.

Note: Swift and Its Discontents

Justice Story’s opinion quotes the Roman statesman and philosopher

Cicero for the proposition that the common law cannot differ from state

to state. The cited passageCicero, On the Republic, Book III, § 22

summarizes the natural law paradigm:

True law is right reason in agreement with nature; it is of universal application, unchanging and everlasting; It is a sin to try to alter this law, nor is it allowable to attempt to repeal any part of it, and it is impossible to abolish it entirely. We cannot be freed from its obligations by senate or people, and we need not look outside ourselves for an expounder or interpreter of it. And there will not be different laws at Rome and at Athens, or different laws now and in the future, but one eternal and unchangeable law will be valid for all nations and all times, and there will be one master and ruler, that is, God, over us all, for he is the author of this law, its promulgator, and its enforcing judge. Whoever is disobedient is fleeing from himself and denying his human nature, and by reason of this very fact he will suffer the worst penalties, even if he escapes what is commonly considered punishment.

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the legal field

experienced a paradigm shift,A paradigm shift is a transformation in the fundamental

assumptions, theories, and practice of a scientific or professional

community. “When the transition is completed, the profession will have

changed its view of the field, its methods, and its goals.” Thomas S.

Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, 84-85 (4th

ed. 2012).

with concepts and methods associated with legal positivism,

realism,

and pragmatism

challenging the previously dominant paradigm of natural law and

formalism. Cases like Erie and International Shoe,

along with the adoption of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, were

significant moments in this jurisprudential revolution.See, e.g. George Rutherglen, International Shoe and the

Legacy of Legal Realism, 2001 Supreme Court Review 347 (2001); Logan

E. Sawyer III, Jurisdiction, Jurisprudence and Legal Change:

Sociological Jurisprudence and the Road to International Shoe, 10 George

Mason Law Review 39 (2001); David Marcus, The Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure and Legal Realism as a Jurisprudence of Law Reform, 44 Georgia

Law Review 433 (2009); William R. Casto, The Erie Doctrine and the

Structure of Constitutional Revolutions, 62 Tulane Law Review 56

(1987).

Among those leading the charge was Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., whose work as a legal scholar and opinions as a Supreme Court Justice advanced a positivist understanding of law and pragmatist approach to judicial decision-making, and laid the groundwork for overturning Swift.

Oliver Wendall Holmes, The Common Law, 1-2 (1881):

The life of the law has not been logic: it has been experience. The felt necessities of the time, the prevalent moral and political theories, intuitions of public policy, avowed or unconscious, even the prejudices which judges share with their fellow-men, have had a good deal more to do than the syllogism in determining the rules by which men should be governed. The law embodies the story of a nation’s development through many centuries, and it cannot be dealt with as if it contained only the axioms and corollaries of a book of mathematics. In order to know what it is, we must know what it has been, and what it tends to become. We must alternately consult history and existing theories of legislation. But the most difficult labor will be to understand the combination of the two into new products at every stage. The substance of the law at any given time pretty nearly corresponds, so far as it goes, with what is then understood to be convenient; but its form and machinery, and the degree to which it is able to work out desired results, depend very much upon its past.

Southern Pacific Co. v. Jensen, 244 U.S. 205 (1917) (Holmes, J. dissenting):

The common law is not a brooding omnipresence in the sky but the articulate voice of some sovereign or quasi-sovereign that can be identified; although some decisions with which I have disagreed seem to me to have forgotten the fact. It always is the law of some State.

Kuhn v. Fairmont Coal Co., 215 US 349, 370-372 (1910) (Holmes, J., dissenting):

I admit that plenty of language can be found in the earlier cases to support the present decision. That is not surprising in view of the uncertainty and vacillation of the theory upon which Swift v. Tyson, and the later extensions of its doctrine have proceeded. But I suppose it will be admitted on the other side that even the independent jurisdiction of the Circuit Courts of the United States is a jurisdiction only to declare the law, at least in a case like the present, and only to declare the law of the State. It is not an authority to make it. Swift v. Tyson was justified on the ground that that was all that the state courts did. But as has been pointed out by a recent accomplished and able writer, that fiction had to be abandoned and was abandoned when this court came to decide the municipal bond cases, beginning with Gelpcke v. Dubuque. In those cases the court recognized the fact that decisions of state courts of last resort make law for the State. The principle is that a change of judicial decision after a contract has been made on the faith of an earlier one the other way is a change of the law.

The cases of the class to which I refer have not stood on the ground that this court agreed with the first decision, but on the ground that the state decision made the law for the State, and therefore should be given only a prospective operation when contracts had been entered into under the law as earlier declared. In various instances this court has changed its decision or rendered different decisions on similar facts arising in different States in order to conform to what is recognized as the local law.

Whether Swift v. Tyson can be reconciled with Gelpcke v. Dubuque, I do not care to enquire. I assume both cases to represent settled doctrines, whether reconcilable or not. But the moment you leave those principles which it is desirable to make uniform throughout the United States and which the decisions of this court tend to make uniform, obviously it is most undesirable for the courts of the United States to appear as interjecting an occasional arbitrary exception to a rule that in every other case prevails. I never yet have heard a statement of any reason justifying the power, and I find it hard to imagine one. I know of no authority in this court to say that in general state decisions shall make law only for the future. Judicial decisions have had retrospective operation for near a thousand years. It is said that we must exercise our independent judgment — but as to what? Surely as to the law of the States. Whence does that law issue? Certainly not from us. But it does issue and has been recognized by this court as issuing from the state courts as well as from the state legislatures. When we know what the source of the law has said that it shall be, our authority is at an end. The law of a State does not become something outside of the state court and independent of it by being called the common law. Whatever it is called it is the law as declared by the state judges and nothing else.

If, as I believe, my reasoning is correct, it justifies our stopping when we come to a kind of case that by nature and necessity is peculiarly local, and one as to which the latest intimations and indeed decisions of this court are wholly in accord with what I think to be sound law. To administer a different law is “to introduce into the jurisprudence of the State of Illinois the discordant elements of a substantial right which is protected in one set of courts and denied in the other, with no superior to decide which is right.” It is admitted that we are bound by a settled course of decisions, irrespective of contract, because they make the law. I see no reason why we are less bound by a single one.

Black & White Taxicab Co. v. Brown & Yellow Taxicab Co., 279 U.S. 518, 532-536 (1928) (Holmes, J., dissenting):

This is a suit brought by The Brown and Yellow Taxicab and Transfer Company, as plaintiff, to prevent The Black and White Taxicab and Transfer Company, from interfering with the carrying out of a contract between the plaintiff and the other defendant, The Louisville and Nashville Railroad Company. The Circuit Court of Appeals, affirming a decree of the District Court, granted an injunction and upheld this contract. It expressly recognized that the decisions of the Kentucky Courts held that in Kentucky a railroad company could not grant such rights, but this being a ‘question of general law’ it went its own way regardless of the Courts of this State.

The Circuit Court of Appeals had so considerable a tradition behind it in deciding as it did that if I did not regard the case as exceptional I should not feel warranted in presenting my own convictions again after having stated them in Kuhn v. Fairmont Coal Company. But the question is important and in my opinion the prevailing doctrine has been accepted upon a subtle fallacy that never has been analyzed. If I am right the fallacy has resulted in an unconstitutional assumption of powers by the Courts of the United States which no lapse of time or respectable array of opinion should make us hesitate to correct. Therefore I think it proper to state what I think the fallacy is. — The often repeated proposition of this and the lower Courts is that the parties are entitled to an independent judgment on matters of general law. By that phrase is meant matters that are not governed by any law of the United States or by any statute of the State — matters that in States other than Louisiana are governed in most respects by what is called the common law. It is through this phrase that what I think the fallacy comes in.

Books written about any branch of the common law treat it as a unit, cite cases from this Court, from the Circuit Courts of Appeals, from the State Courts, from England and the Colonies of England indiscriminately, and criticize them as right or wrong according to the writer’s notions of a single theory. It is very hard to resist the impression that there is one august corpus, to understand which clearly is the only task of any Court concerned. If there were such a transcendental body of law outside of any particular State but obligatory within it unless and until changed by statute, the Courts of the United States might be right in using their independent judgment as to what it was. But there is no such body of law. The fallacy and illusion that I think exist consist in supposing that there is this outside thing to be found. Law is a word used with different meanings, but law in the sense in which courts speak of it today does not exist without some definite authority behind it. The common law so far as it is enforced in a State, whether called common law or not, is not the common law generally but the law of that State existing by the authority of that State without regard to what it may have been in England or anywhere else. It may be adopted by statute in place of another system previously in force. But a general adoption of it does not prevent the State Courts from refusing to follow the English decisions upon a matter where the local conditions are different. It may be changed by statute, as is done every day. It may be departed from deliberately by judicial decisions, as with regard to water rights, in States where the common law generally prevails. Louisiana is a living proof that it need not be adopted at all. Whether and how far and in what sense a rule shall be adopted whether called common law or Kentucky law is for the State alone to decide.

If within the limits of the Constitution a State should declare one of the disputed rules of general law by statute there would be no doubt of the duty of all Courts to bow, whatever their private opinions might be. I see no reason why it should have less effect when it speaks by its other voice. If a state constitution should declare that on all matters of general law the decisions of the highest Court should establish the law until modified by statute or by a later decision of the same Court, I do not perceive how it would be possible for a Court of the United States to refuse to follow what the State Court decided in that domain. But when the constitution of a State establishes a Supreme Court it by implication does make that declaration as clearly as if it had said it in express words, so far as it is not interfered with by the superior power of the United States. The Supreme Court of a State does something more than make a scientific inquiry into a fact outside of and independent of it. It says, with an authority that no one denies, except when a citizen of another State is able to invoke an exceptional jurisdiction, that thus the law is and shall be. Whether it be said to make or to declare the law, it deals with the law of the State with equal authority however its function may be described.

Mr. Justice Story in Swift v. Tyson, evidently under the tacit domination of the fallacy to which I have referred, devotes some energy to showing that the Rules of Decision Act refers only to statutes when it provides that except as excepted the laws of the several States shall be regarded as rules of decision in trials at common law in Courts of the United States. An examination of the original document by a most competent hand has shown that Mr. Justice Story probably was wrong if anyone is interested to inquire what the framers of the instrument meant. 37 Harvard Law Review, 49, at pp. 81-88. But this question is deeper than that; it is a question of the authority by which certain particular acts, here the grant of exclusive privileges in a railroad station, are governed. In my opinion the authority and only authority is the State, and if that be so, the voice adopted by the State as its own should utter the last word. I should leave Swift v. Tyson undisturbed, as I indicated in Kuhn v. Fairmont Coal Co., but I would not allow it to spread the assumed dominion into new fields.

In view of what I have said it is not necessary for me to give subordinate and narrower reasons for my opinion that the decision below should be reversed. But there are adequate reasons short of what I think should be recognized. This is a question concerning the lawful use of land in Kentucky by a corporation chartered by Kentucky. The policy of Kentucky with regard to it has been settled in Kentucky for more than thirty-five years. Even under the rule that I combat, it has been recognized that a settled line of state decisions was conclusive to establish a rule of property or the public policy of the State. I should have supposed that what arrangements could or could not be made for the use of a piece of land was a purely local question, on which, if on anything, the State should have its own way and the State Courts should be taken to declare what the State wills.

Holmes stepped down from the Court in 1932 and died in 1935. Three years later, the Court, in an opinion by Justice Louis Brandeis (another important figure in legal pragmatism and realism) overturned Swift and adopted a positivist interpretation of the Rules of Decision Act.

Erie R.R. Co. v. Tompkins, 304 U.S. 64 (1938)

Justice BRANDEIS delivered the opinion of the Court.

The question for decision is whether the oft-challenged doctrine of Swift v. Tyson shall now be disapproved.

Tompkins, a citizen of Pennsylvania, was injured on a dark night by a passing freight train of the Erie Railroad Company while walking along its right of way at Hughestown in that State. He claimed that the accident occurred through negligence in the operation, or maintenance, of the train; that he was rightfully on the premises as licensee because on a commonly used beaten footpath which ran for a short distance alongside the tracks; and that he was struck by something which looked like a door projecting from one of the moving cars. To enforce that claim he brought an action in the federal court for southern New York, which had jurisdiction because the company is a corporation of that State. It denied liability; and the case was tried by a jury.

The Erie insisted that its duty to Tompkins was no greater than that owed to a trespasser. It contended, among other things, that its duty to Tompkins, and hence its liability, should be determined in accordance with the Pennsylvania law; that under the law of Pennsylvania, as declared by its highest court, persons who use pathways along the railroad right of way—that is a longitudinal pathway as distinguished from a crossing—are to be deemed trespassers; and that the railroad is not liable for injuries to undiscovered trespassers resulting from its negligence, unless it be wanton or wilful. Tompkins denied that any such rule had been established by the decisions of the Pennsylvania courts; and contended that, since there was no statute of the State on the subject, the railroad’s duty and liability is to be determined in federal courts as a matter of general law.

The trial judge refused to rule that the applicable law precluded recovery. The jury brought in a verdict of $30,000; and the judgment entered thereon was affirmed by the Circuit Court of Appeals, which held that it was unnecessary to consider whether the law of Pennsylvania was as contended, because the question was one not of local, but of general, law and that “upon questions of general law the federal courts are free, in the absence of a local statute, to exercise their independent judgment as to what the law is; and it is well settled that the question of the responsibility of a railroad for injuries caused by its servants is one of general law. Where the public has made open and notorious use of a railroad right of way for a long period of time and without objection, the company owes to persons on such permissive pathway a duty of care in the operation of its trains. It is likewise generally recognized law that a jury may find that negligence exists toward a pedestrian using a permissive path on the railroad right of way if he is hit by some object projecting from the side of the train.”

The Erie had contended that application of the Pennsylvania rule was required, among other things, by the Rules of Decision Act, which provides:

The laws of the several States, except where the Constitution, treaties, or statutes of the United States otherwise require or provide, shall be regarded as rules of decision in trials at common law, in the courts of the United States, in cases where they apply.

Because of the importance of the question whether the federal court was free to disregard the alleged rule of the Pennsylvania common law, we granted certiorari.

First. Swift v. Tyson held that federal courts exercising jurisdiction on the ground of diversity of citizenship need not, in matters of general jurisprudence, apply the unwritten law of the State as declared by its highest court; that they are free to exercise an independent judgment as to what the common law of the State is—or should be; and that, as there stated by Mr. Justice Story:

the true interpretation of the thirty-fourth section limited its application to state laws strictly local, that is to say, to the positive statutes of the state, and the construction thereof adopted by the local tribunals, and to rights and titles to things having a permanent locality, such as the rights and titles to real estate, and other matters immovable and intraterritorial in their nature and character. It never has been supposed by us, that the section did apply, or was intended to apply, to questions of a more general nature, not at all dependent upon local statutes or local usages of a fixed and permanent operation, as, for example, to the construction of ordinary contracts or other written instruments, and especially to questions of general commercial law, where the state tribunals are called upon to perform the like functions as ourselves, that is, to ascertain upon general reasoning and legal analogies, what is the true exposition of the contract or instrument, or what is the just rule furnished by the principles of commercial law to govern the case.

The Court in applying the Rules

of Decision Act to equity cases, in Mason v. United States,

260 U.S. 545, 559, said: “The statute, however, is merely declarative of

the rule which would exist in the absence of the statute.” The federal

courts assumed, in the broad field of “general law,” the power to

declare rules of decision which Congress was confessedly without power

to enact as statutes. Doubt was repeatedly expressed as to the

correctness of the construction given the Rules of Decision Act, and as

to the soundness of the rule which it introduced. But it was the more

recent research of a competent scholar, who examined the original

document, which established that the construction given to it by the

Court was erroneous; and that the purpose of the section was merely to

make certain that, in all matters except those in which some federal law

is controlling, the federal courts exercising jurisdiction in diversity

of citizenship cases would apply as their rules of decision the law of

the State, unwritten as well as written.(n.5 in opinion) Charles Warren, New Light on the

History of the Federal Judiciary Act of 1789 (1923) 37 Harv. L. Rev. 49,

51-52, 81-88, 108.

Criticism of the doctrine became widespread after the decision of Black & White Taxicab Co. v. Brown & Yellow Taxicab Co., 276 U.S. 518 (1928). There, Brown and Yellow, a Kentucky corporation owned by Kentuckians, and the Louisville and Nashville Railroad, also a Kentucky corporation, wished that the former should have the exclusive privilege of soliciting passenger and baggage transportation at the Bowling Green, Kentucky, railroad station; and that the Black and White, a competing Kentucky corporation, should be prevented from interfering with that privilege. Knowing that such a contract would be void under the common law of Kentucky, it was arranged that the Brown and Yellow reincorporate under the law of Tennessee, and that the contract with the railroad should be executed there. The suit was then brought by the Tennessee corporation in the federal court for western Kentucky to enjoin competition by the Black and White; an injunction issued by the District Court was sustained by the Court of Appeals; and this Court, citing many decisions in which the doctrine of Swift v. Tyson had been applied, affirmed the decree.

Second. Experience in applying the doctrine of Swift v. Tyson, had revealed its defects, political and social; and the benefits expected to flow from the rule did not accrue. Persistence of state courts in their own opinions on questions of common law prevented uniformity; and the impossibility of discovering a satisfactory line of demarcation between the province of general law and that of local law developed a new well of uncertainties.

On the other hand, the mischievous results of the doctrine had become apparent. Diversity of citizenship jurisdiction was conferred in order to prevent apprehended discrimination in state courts against those not citizens of the State. Swift v. Tyson introduced grave discrimination by non-citizens against citizens. It made rights enjoyed under the unwritten “general law” vary according to whether enforcement was sought in the state or in the federal court; and the privilege of selecting the court in which the right should be determined was conferred upon the non-citizen. Thus, the doctrine rendered impossible equal protection of the law. In attempting to promote uniformity of law throughout the United States, the doctrine had prevented uniformity in the administration of the law of the State.

The discrimination resulting became in practice far-reaching. This resulted in part from the broad province accorded to the so-called “general law” as to which federal courts exercised an independent judgment. In addition to questions of purely commercial law, “general law” was held to include the obligations under contracts entered into and to be performed within the State, the extent to which a carrier operating within a State may stipulate for exemption from liability for his own negligence or that of his employee; the liability for torts committed within the State upon persons resident or property located there, even where the question of liability depended upon the scope of a property right conferred by the State; and the right to exemplary or punitive damages. Furthermore, state decisions construing local deeds, mineral conveyances, and even devises of real estate were disregarded.

In part the discrimination resulted from the wide range of persons held entitled to avail themselves of the federal rule by resort to the diversity of citizenship jurisdiction. Through this jurisdiction individual citizens willing to remove from their own State and become citizens of another might avail themselves of the federal rule. And, without even change of residence, a corporate citizen of the State could avail itself of the federal rule by re-incorporating under the laws of another State, as was done in the Taxicab case.

The injustice and confusion incident to the doctrine of Swift v. Tyson have been repeatedly urged as reasons for abolishing or limiting diversity of citizenship jurisdiction. Other legislative relief has been proposed. If only a question of statutory construction were involved, we should not be prepared to abandon a doctrine so widely applied throughout nearly a century. But the unconstitutionality of the course pursued has now been made clear and compels us to do so.

Third. Except in matters governed by the Federal Constitution or by Acts of Congress, the law to be applied in any case is the law of the State. And whether the law of the State shall be declared by its Legislature in a statute or by its highest court in a decision is not a matter of federal concern. There is no federal general common law. Congress has no power to declare substantive rules of common law applicable in a State whether they be local in their nature or “general,” be they commercial law or a part of the law of torts. And no clause in the Constitution purports to confer such a power upon the federal courts. As stated by Mr. Justice Field when protesting in Baltimore & Ohio R. Co. v. Baugh, 149 U.S. 368, 401, against ignoring the Ohio common law of fellow servant liability:

I am aware that what has been termed the general law of the country—which is often little less than what the judge advancing the doctrine thinks at the time should be the general law on a particular subject—has been often advanced in judicial opinions of this court to control a conflicting law of a State. I admit that learned judges have fallen into the habit of repeating this doctrine as a convenient mode of brushing aside the law of a State in conflict with their views. And I confess that, moved and governed by the authority of the great names of those judges, I have, myself, in many instances, unhesitatingly and confidently, but I think now erroneously, repeated the same doctrine. But, notwithstanding the great names which may be cited in favor of the doctrine, and notwithstanding the frequency with which the doctrine has been reiterated, there stands, as a perpetual protest against its repetition, the Constitution of the United States, which recognizes and preserves the autonomy and independence of the States—independence in their legislative and independence in their judicial departments. Supervision over either the legislative or the judicial action of the States is in no case permissible except as to matters by the Constitution specifically authorized or delegated to the United States. Any interference with either, except as thus permitted, is an invasion of the authority of the State and, to that extent, a denial of its independence.

The fallacy underlying the rule declared in Swift v. Tyson is made clear by Mr. Justice Holmes. The doctrine rests upon the assumption that there is “a transcendental body of law outside of any particular State but obligatory within it unless and until changed by statute,” that federal courts have the power to use their judgment as to what the rules of common law are; and that in the federal courts “the parties are entitled to an independent judgment on matters of general law”:

but law in the sense in which courts speak of it today does not exist without some definite authority behind it. The common law so far as it is enforced in a State, whether called common law or not, is not the common law generally but the law of that State existing by the authority of that State without regard to what it may have been in England or anywhere else. “the authority and only authority is the State, and if that be so, the voice adopted by the State as its own [whether it be of its Legislature or of its Supreme Court] should utter the last word.”

Thus the doctrine of Swift v. Tyson, is, as Mr. Justice Holmes said, “an unconstitutional assumption of powers by courts of the United States which no lapse of time or respectable array of opinion should make us hesitate to correct.” In disapproving that doctrine we do not hold unconstitutional § 34 of the Federal Judiciary Act of 1789 or any other Act of Congress. We merely declare that in applying the doctrine this Court and the lower courts have invaded rights which in our opinion are reserved by the Constitution to the several States.

Fourth.On remand, the Court of Appeals concluded that,

“Under the Pennsylvania law, the defendant owed no duty to the plaintiff

except to refrain from wanton or wilful injury.” Because Tompkins

neither alleged nor proved that the Railroad acted wantonly or wilfully,

the case was remanded to the trial court with directions to enter

judgment in favor of the Railroad. 98 F.2d 49 (2d Cir. 1938). For a more

detailed account of the incident (including photos of Tompkins before

and after his unfortunate encounter with the train), see Brian Frye, “The Ballad of Harry

Tompkins”.

The defendant contended that by the common law of

Pennsylvania as declared by its highest court [ * * * ], the only duty

owed to the plaintiff was to refrain from wilful or wanton injury. The

plaintiff denied that such is the Pennsylvania law. In support of their

respective contentions the parties discussed and cited many decisions of

the Supreme Court of the State. The Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that

the question of liability is one of general law; and on that ground

declined to decide the issue of state law. As we hold this was error,

the judgment is reversed and the case remanded to it for further

proceedings in conformity with our opinion.

Substance and Procedure under Erie

The underlying issue in Erie was one of substantive law: the standard of care that the Railroad owed Tompkins. In a concurring opinion, Justice Reed suggested that on matters of procedure, federal courts were not bound to follow state law:

The line between procedural and substantive law is hazy but no one doubts federal power over procedure. The Judiciary Article and the “necessary and proper” clause of Article One may fully authorize legislation, such as this section of the Judiciary Act.

In the aftermath of Erie, the Court sought to provide an answer to the question of how to draw the line between substance and procedure:

Guaranty Trust Co. of New York v. York, 326 U.S. 99 (1945)

York sued Guaranty Trust for breach of fiduciary duty. The issue was

whether, “in a suit brought on the equity side“The term ‘equity’ refers to a particular set of

remedies and associated procedures involved with civil law. These

equitable doctrines and procedures are distinguished from ‘legal’ ones.

While legal remedies typically involve monetary damages, equitable

relief typically refers to injunctions, specific performance, or

vacatur. A court will usually award equitable remedies when a legal

remedy is insufficient or inadequate.” Wex Legal Dictionary

The Federal Rules of Civil Procedure eliminated the procedural

distinction between “law” and “equity” suits, and most state judicial

systems have followed suit.

of a federal district court that court is required to

apply the State statute of limitations that would govern like suits in

the courts of a State where the federal court is sitting even though the

exclusive basis of federal jurisdiction is diversity of citizenship.” If

so, the suit would be dismissed as untimely. This turned on whether

application of the state statute of limitations to bar “a claim created

by the States is a matter of ‘substantive rights’ to be respected by a

federal court of equity when that court’s jurisdiction is dependent on

the fact that there is a State-created right, or is such statute of ’a

mere remedial character, which a federal court may disregard?”

Rather than mechanically applying the labels “substance” and “procedure”, the Court took a pragmatic approach focused on whether application of a different rule would yield a different outcome.

Here we are dealing with a right to recover derived not from the United States but from one of the States. When, because the plaintiff happens to be a non-resident, such a right is enforceable in a federal as well as in a State court, the forms and mode of enforcing the right may at times, naturally enough, vary because the two judicial systems are not identic. But since a federal court adjudicating a State-created right solely because of the diversity of citizenship of the parties is for that purpose, in effect, only another court of the State, it cannot afford recovery if the right to recover is made unavailable by the State nor can it substantially affect the enforcement of the right as given by the State.

And so the question is not whether a statute of limitations is deemed a matter of “procedure” in some sense. The question is whether such a statute concerns merely the manner and the means by which a right to recover, as recognized by the State, is enforced, or whether such statutory limitation is a matter of substance in the aspect that alone is relevant to our problem, namely, does it significantly affect the result of a litigation for a federal court to disregard a law of a State that would be controlling in an action upon the same claim by the same parties in a State court?

It is therefore immaterial whether statutes of limitation are characterized either as “substantive” or “procedural” in State court opinions in any use of those terms unrelated to the specific issue before us. Erie R. Co. v. Tompkins was not an endeavor to formulate scientific legal terminology. It expressed a policy that touches vitally the proper distribution of judicial power between State and federal courts. In essence, the intent of that decision was to insure that, in all cases where a federal court is exercising jurisdiction solely because of the diversity of citizenship of the parties, the outcome of the litigation in the federal court should be substantially the same, so far as legal rules determine the outcome of a litigation, as it would be if tried in a State court. The nub of the policy that underlies Erie R. Co. v. Tompkins is that for the same transaction the accident of a suit by a non-resident litigant in a federal court instead of in a State court a block away should not lead to a substantially different result.

Plainly enough, a statute that would completely bar recovery in a suit if brought in a State court bears on a State-created right vitally and not merely formally or negligibly. As to consequences that so intimately affect recovery or non-recovery a federal court in a diversity case should follow State law.

Ragan v. Merchants Transfer & Warehouse Co., 337 U.S. 530 (1949)

Ragan sued Merchants Transfer for injuries resulting from a traffic accident. A two-year statute of limitations under state law applied. The plaintiff filed the complaint in federal court less than two years after the accident, but did not serve the complaint on the defendant until more than two years had passed. Relying on Fed. R. Civ. P. Rule 3 (“A civil action is commenced by filing a complaint with the court.”), the plaintiff argued that filing the complaint was sufficient to satisfy the statute of limitations. The defendant argued that the federal court must follow state law, under which the statute of limitations was not satisfied unless the suit was both filed and served within the allotted time.

As in Guaranty Trust, the Court focused on whether applying different rules in state and federal court would yield different outcomes. Once again, the Court held that the federal court must follow state law, under which the plaintiff’s right to relief would be extinguished.

Woods v. Interstate Realty, 337 U.S. 535 (1949) and Cohen v. Beneficial Indust. Loan Corp, 337 U.S. 541 (1949)

In these two cases, decided together with Ragan, the Court likewise held that the federal court must apply state law rules where a contrary federal rule would have yielded different outcomes. Woods v. Interstate Realty (State rule, barring unqualified business from appearing in state court, applies in federal diversity action); Cohen v. Beneficial Indust. Loan Corp, (State rule, requiring bond in shareholder derivative suit, applies in federal diversity action, despite lack of bond requirement in FRCP Rule 23.1).

Byrd v. Blue Ridge Rural Electric Cooperative, Inc., 356 U.S. 525 (1958)

Justice BRENNAN delivered the opinion of the Court.

This case was brought in the District Court for the Western District of South Carolina. Jurisdiction was based on diversity of citizenship. 28 U. S. C. § 1332. The petitioner, a resident of North Carolina, sued respondent, a South Carolina corporation, for damages for injuries allegedly caused by the respondent’s negligence. He had judgment on a jury verdict. The Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit reversed and directed the entry of judgment for the respondent. We granted certiorari and subsequently ordered reargument.

The respondent is in the business of selling electric power to subscribers in rural sections of South Carolina. The petitioner was employed as a lineman in the construction crew of a construction contractor. The contractor, R. H. Bouligny, Inc., held a contract with the respondent in the amount of $334,300 for the building of some 24 miles of new power lines, the reconversion to higher capacities of about 88 miles of existing lines, and the construction of 2 new substations and a breaker station. The petitioner was injured while connecting power lines to one of the new substations.

One of respondent’s affirmative defenses was that, under the South Carolina Workmen’s Compensation Act, the petitioner—because the work contracted to be done by his employer was work of the kind also done by the respondent’s own construction and maintenance crews—had the status of a statutory employee of the respondent and was therefore barred from suing the respondent at law because obliged to accept statutory compensation benefits as the exclusive remedy for his injuries. Two questions concerning this defense are before us: (1) whether the Court of Appeals erred in directing judgment for respondent without a remand to give petitioner an opportunity to introduce further evidence; and (2) whether petitioner, state practice notwithstanding, is entitled to a jury determination of the factual issues raised by this defense.

I.

The Supreme Court of South Carolina has held that there is no particular formula by which to determine whether an owner is a statutory employer under [the South Carolina workers’ compensation statute]:

while the language of the statute is plain and unambiguous, there are so many different factual situations which may arise that no easily applied formula can be laid down for the determination of all cases. In other words, ‘it is often a matter of extreme difficulty to decide whether the work in a given case falls within the designation of the statute. It is in each case largely a question of degree and of fact.’

[The trial judge concluded, based on his interpretation of the South Carolina statute and the evidence presented, that Byrd was not a statutory employee of Blue Ridge and thus denied Blue Ridge’s motion to dismiss based on the workers’ compensation bar.]

The Court of Appeals disagreed with the District Court’s construction of [the statute]. Relying on the decisions of the Supreme Court of South Carolina, the Court of Appeals held that the statute granted respondent immunity from the action if the proofs established that the respondent’s own crews had constructed lines and substations which, like the work contracted to the petitioner’s employer, were necessary for the distribution of the electric power which the respondent was in the business of selling. We ordinarily accept the interpretation of local law by the Court of Appeals, and do so readily here since neither party now disputes the interpretation.

However, instead of ordering a new trial at which the petitioner might offer his own proof pertinent to a determination according to the correct interpretation, the Court of Appeals made its own determination on the record and directed a judgment for the respondent.

While the matter is not adverted to in the court’s opinion, implicit in the direction of verdict is the holding that the petitioner, although having no occasion to do so under the District Court’s erroneous construction of the statute, was not entitled to an opportunity to meet the respondent’s case under the correct interpretation.

We believe that the Court of Appeals erred. The petitioner is entitled to have the question determined in the trial court. This would be necessary even if petitioner offered no proof of his own. Although the respondent’s evidence was sufficient to withstand the motion under the meaning given the statute by the Court of Appeals, it presented a fact question, which, in the circumstances of this case is properly to be decided by a jury. the jury on the entire record—consistent with the view of the South Carolina cases that this question is in each case largely one of degree and of fact—might reasonably reach an opposite conclusion from the Court of Appeals as to the ultimate fact whether the respondent was a statutory employer.

At all events, the petitioner is plainly entitled to have an opportunity to try the issue under the Court of Appeals’ interpretation.

II.

A question is also presented as to whether on remand the factual issue is to be decided by the judge or by the jury. The respondent argues on the basis of the decision of the Supreme Court of South Carolina in Adams v. Davison-Paxon Co. that the issue of immunity should be decided by the judge and not by the jury. That was a negligence action brought in the state trial court against a store owner by an employee of an independent contractor who operated the store’s millinery department. The trial judge denied the store owner’s motion for a directed verdict made upon the ground that [the workers’ compensation statute] barred the plaintiff’s action. The jury returned a verdict for the plaintiff. The South Carolina Supreme Court reversed, holding that it was for the judge and not the jury to decide on the evidence whether the owner was a statutory employer, and that the store owner had sustained his defense. The court rested its holding on decisions involving judicial review of the Industrial Commission.

The respondent argues that this state-court decision governs the present diversity case and “divests the jury of its normal function” to decide the disputed fact question of the respondent’s immunity under [the workers’ compensation statute]. This is to contend that the federal court is bound under Erie R. Co. v. Tompkins to follow the state court’s holding to secure uniform enforcement of the immunity created by the State.

First. It was decided in Erie R. Co. v. Tompkins that the federal courts in diversity cases must respect the definition of state-created rights and obligations by the state courts. We must, therefore, first examine the rule in Adams v. Davison-Paxon Co. to determine whether it is bound up with these rights and obligations in such a way that its application in the federal court is required.

The Workmen’s Compensation Act is administered in South Carolina by its Industrial Commission. The South Carolina courts hold that, on judicial review of actions of the Commission under [the Act], the question whether the claim of an injured workman is within the Commission’s jurisdiction is a matter of law for decision by the court, which makes its own findings of fact relating to that jurisdiction. The South Carolina Supreme Court states no reasons in Adams v. Davison-Paxon Co. why, although the jury decides all other factual issues raised by the cause of action and defenses, the jury is displaced as to the factual issue raised by the affirmative defense under [the workers’ compensation statute]. The decisions cited to support the holding are concerned solely with defining the scope and method of judicial review of the Industrial Commission. A State may, of course, distribute the functions of its judicial machinery as it sees fit. The decisions relied upon, however, furnish no reason for selecting the judge rather than the jury to decide this single affirmative defense in the negligence action. They simply reflect a policy that administrative determination of “jurisdictional facts” should not be final but subject to judicial review. The conclusion is inescapable that the Adams holding is grounded in the practical consideration that the question had therefore come before the South Carolina courts from the Industrial Commission and the courts had become accustomed to deciding the factual issue of immunity without the aid of juries. We find nothing to suggest that this rule was announced as an integral part of the special relationship created by the statute. Thus the requirement appears to be merely a form and mode of enforcing the immunity, and not a rule intended to be bound up with the definition of the rights and obligations of the parties.

Second. But cases following Erie have evinced a broader policy to the effect that the federal courts should conform as near as may be—in the absence of other considerations—to state rules even of form and mode where the state rules may bear substantially on the question whether the litigation would come out one way in the federal court and another way in the state court if the federal court failed to apply a particular local rule. Concededly the nature of the tribunal which tries issues may be important in the enforcement of the parcel of rights making up a cause of action or defense, and bear significantly upon achievement of uniform enforcement of the right. It may well be that in the instant personal-injury case the outcome would be substantially affected by whether the issue of immunity is decided by a judge or a jury. Therefore, were “outcome” the only consideration, a strong case might appear for saying that the federal court should follow the state practice.

But there are affirmative countervailing considerations at work here. The federal system is an independent system for administering justice to litigants who properly invoke its jurisdiction. An essential characteristic of that system is the manner in which, in civil common-law actions, it distributes trial functions between judge and jury and, under the influence—if not the command—of the Seventh Amendment, assigns the decisions of disputed questions of fact to the jury. The policy of uniform enforcement of state-created rights and obligations cannot in every case exact compliance with a state rule—not bound up with rights and obligations—which disrupts the federal system of allocating functions between judge and jury. Thus the inquiry here is whether the federal policy favoring jury decisions of disputed fact questions should yield to the state rule in the interest of furthering the objective that the litigation should not come out one way in the federal court and another way in the state court.

We think that in the circumstances of this case the federal court should not follow the state rule. It cannot be gainsaid that there is a strong federal policy against allowing state rules to disrupt the judge-jury relationship in the federal courts. In Herron v. Southern Pacific Co., 283 U.S. 91 (1931), the trial judge in a personal-injury negligence action brought in the District Court for Arizona on diversity grounds directed a verdict for the defendant when it appeared as a matter of law that the plaintiff was guilty of contributory negligence. The federal judge refused to be bound by a provision of the Arizona Constitution which made the jury the sole arbiter of the question of contributory negligence. This Court sustained the action of the trial judge, holding that “state laws cannot alter the essential character or function of a federal court” because that function “is not in any sense a local matter, and state statutes which would interfere with the appropriate performance of that function are not binding upon the federal court under either the Conformity Act or the ‘rules of decision’ Act.” Perhaps even more clearly in light of the influence of the Seventh Amendment, the function assigned to the jury “is an essential factor in the process for which the Federal Constitution provides.” Concededly the Herron case was decided before Erie R. Co. v. Tompkins, but even when Swift v. Tyson was governing law and allowed federal courts sitting in diversity cases to disregard state decisional law, it was never thought that state statutes or constitutions were similarly to be disregarded. Yet Herron held that state statutes and constitutional provisions could not disrupt or alter the essential character or function of a federal court.

Third. We have discussed the problem upon the assumption that the outcome of the litigation may be substantially affected by whether the issue of immunity is decided by a judge or a jury. But clearly there is not present here the certainty that a different result would follow, or even the strong possibility that this would be the case. There are factors present here which might reduce that possibility. The trial judge in the federal system has powers denied the judges of many States to comment on the weight of evidence and credibility of witnesses, and discretion to grant a new trial if the verdict appears to him to be against the weight of the evidence. We do not think the likelihood of a different result is so strong as to require the federal practice of jury determination of disputed factual issues to yield to the state rule in the interest of uniformity of outcome.

The Rules Enabling Act

28 U.S.C. § 2072

Rules of procedure and evidence; power to prescribe

(a) The Supreme Court shall have the power to prescribe general rules of practice and procedure and rules of evidence for cases in the United States district courts (including proceedings before magistrate judges thereof) and courts of appeals.

(b) Such rules shall not abridge, enlarge or modify any substantive right. All laws in conflict with such rules shall be of no further force or effect after such rules have taken effect.

(c) Such rules may define when a ruling of a district court is final for the purposes of appeal under section 1291 of this title.

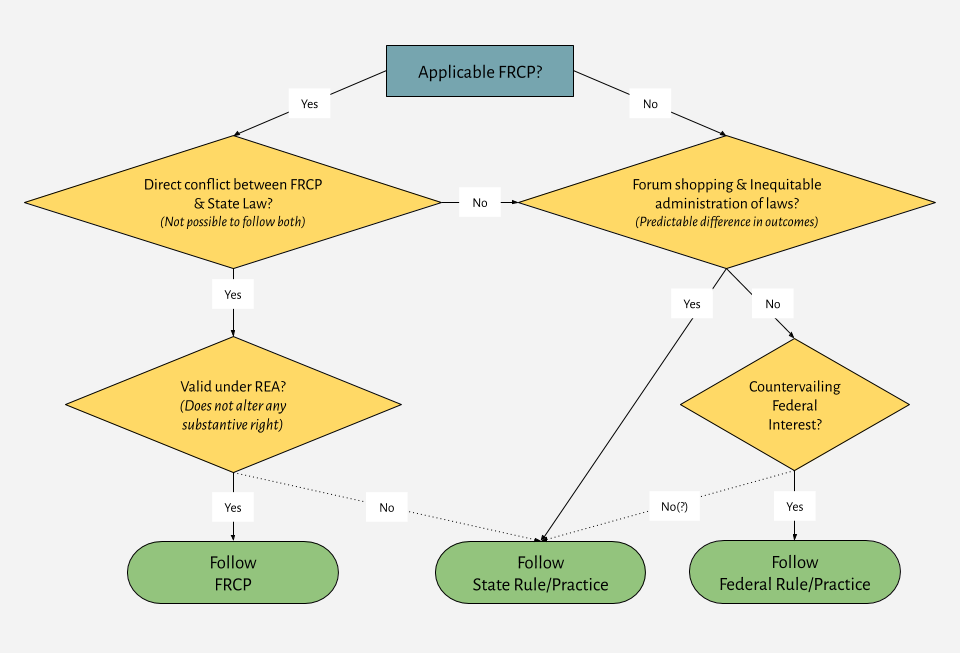

Hanna v. Plumer, 380 U.S. 460 (1965)

Chief Justice WARREN delivered the opinion of the Court.

The question to be decided is whether, in a civil action where the jurisdiction of the United States district court is based upon diversity of citizenship between the parties, service of process shall be made in the manner prescribed by state law or that set forth in Rule 4(d)(1) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.

On February 6, 1963, petitioner, a citizen of Ohio, filed her complaint in the District Court for the District of Massachusetts, claiming damages in excess of $10,000 for personal injuries resulting from an automobile accident in South Carolina, allegedly caused by the negligence of one Louise Plumer Osgood, a Massachusetts citizen deceased at the time of the filing of the complaint. Respondent, Mrs. Osgood’s executor and also a Massachusetts citizen, was named as defendant. On February 8, service was made by leaving copies of the summons and the complaint with respondent’s wife at his residence, concededly in compliance with Rule 4(d)(1), which provides:

The summons and complaint shall be served together. The plaintiff shall furnish the person making service with such copies as are necessary. Service shall be made as follows:

- Upon an individual other than an infant or an incompetent person, by delivering a copy of the summons and of the complaint to him personally or by leaving copies thereof at his dwelling house or usual place of abode with some person of suitable age and discretion then residing therein.

Respondent filed his answer on February 26, alleging, inter alia, that the action could not be maintained because it had been brought “contrary to and in violation of the provisions of Massachusetts General Laws (Ter. Ed.) Chapter 197, Section 9.” That section provides:

Except as provided in this chapter, an executor or administrator shall not be held to answer to an action by a creditor of the deceased which is not commenced within one year from the time of his giving bond for the performance of his trust, or to such an action which is commenced within said year unless before the expiration thereof the writ in such action has been served by delivery in hand upon such executor or administrator or service thereof accepted by him or a notice stating the name of the estate, the name and address of the creditor, the amount of the claim and the court in which the action has been brought has been filed in the proper registry of probate.

On October 17, 1963, the District Court granted respondent’s motion for summary judgment, citing Ragan v. Merchants Transfer Co., 337 U. S. 530, and Guaranty Trust Co. v. York, 326 U. S. 99, in support of its conclusion that the adequacy of the service was to be measured by § 9, with which, the court held, petitioner had not complied. On appeal, petitioner admitted noncompliance with § 9, but argued that Rule 4(d)(1) defines the method by which service of process is to be effected in diversity actions. The Court of Appeals for the First Circuit, finding that “[r]elatively recent amendments [to § 9] evince a clear legislative purpose to require personal notification within the year,” concluded that the conflict of state and federal rules was over “a substantive rather than a procedural matter,” and unanimously affirmed. Because of the threat to the goal of uniformity of federal procedure posed by the decision below, we granted certiorari.

We conclude that the adoption of Rule 4(d)(1), designed to control service of process in diversity actions, neither exceeded the congressional mandate embodied in the Rules Enabling Act nor transgressed constitutional bounds, and that the Rule is therefore the standard against which the District Court should have measured the adequacy of the service. Accordingly, we reverse the decision of the Court of Appeals.

The Rules Enabling Act, 28 U.S.C. § 2072, provides, in pertinent part:

The Supreme Court shall have the power to prescribe, by general rules, the forms of process, writs, pleadings, and motions, and the practice and procedure of the district courts of the United States in civil actions.

Such rules shall not abridge, enlarge or modify any substantive right and shall preserve the right of trial by jury.

Under the cases construing the scope of the Enabling Act, Rule 4(d)(1) clearly passes muster. Prescribing the manner in which a defendant is to be notified that a suit has been instituted against him, it relates to the “practice and procedure of the district courts.”

The test must be whether a rule really regulates procedure,—the judicial process for enforcing rights and duties recognized by substantive law and for justly administering remedy and redress for disregard or infraction of them.

Sibbach v. Wilson & Co., 312 U. S. 1, 14.

In Mississippi Pub. Corp. v. Murphree, 326 U. S. 438, this Court upheld Rule 4(f), which permits service of a summons anywhere within the State (and not merely the district) in which a district court sits:

We think that Rule 4(f) is in harmony with the Enabling Act. Undoubtedly most alterations of the rules of practice and procedure may and often do affect the rights of litigants. Congress’ prohibition of any alteration of substantive rights of litigants was obviously not addressed to such incidental effects as necessarily attend the adoption of the prescribed new rules of procedure upon the rights of litigants who, agreeably to rules of practice and procedure, have been brought before a court authorized to determine their rights. Sibbach v. Wilson & Co. The fact that the application of Rule 4(f) will operate to subject petitioner’s rights to adjudication by the district court for northern Mississippi will undoubtedly affect those rights. But it does not operate to abridge, enlarge or modify the rules of decision by which that court will adjudicate its rights.

Thus were there no conflicting state procedure, Rule 4(d)(1) would clearly control. However, respondent, focusing on the contrary Massachusetts rule, calls to the Court’s attention another line of cases, a line which—like the Federal Rules—had its birth in 1938. Erie R. Co. v. Tompkins held that federal courts sitting in diversity cases, when deciding questions of “substantive” law, are bound by state court decisions as well as state statutes. The broad command of Erie was therefore identical to that of the Enabling Act: federal courts are to apply state substantive law and federal procedural law. However, as subsequent cases sharpened the distinction between substance and procedure, the line of cases following Erie diverged markedly from the line construing the Enabling Act. Guaranty Trust Co. v. York made it clear that Erie-type problems were not to be solved by reference to any traditional or common-sense substance-procedure distinction:

And so the question is not whether a statute of limitations is deemed a matter of ‘procedure’ in some sense. The question is does it significantly affect the result of a litigation for a federal court to disregard a law of a State that would be controlling in an action upon the same claim by the same parties in a State court?

Respondent, by placing primary reliance on York and Ragan, suggests that the Erie doctrine acts as a check on the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, that despite the clear command of Rule 4(d)(1), Erie and its progeny demand the application of the Massachusetts rule. Reduced to essentials, the argument is: (1) Erie, as refined in York, demands that federal courts apply state law whenever application of federal law in its stead will alter the outcome of the case. (2) In this case, a determination that the Massachusetts service requirements obtain will result in immediate victory for respondent. If, on the other hand, it should be held that Rule 4(d)(1) is applicable, the litigation will continue, with possible victory for petitioner. (3) Therefore, Erie demands application of the Massachusetts rule. The syllogism possesses an appealing simplicity, but is for several reasons invalid.

In the first place, it is doubtful that, even if there were no Federal Rule making it clear that in-hand service is not required in diversity actions, the Erie rule would have obligated the District Court to follow the Massachusetts procedure. “Outcome-determination” analysis was never intended to serve as a talisman. Indeed, the message of York itself is that choices between state and federal law are to be made not by application of any automatic, “litmus paper” criterion, but rather by reference to the policies underlying the Erie rule.

The Erie rule is rooted in part in a realization that it would be unfair for the character or result of a litigation materially to differ because the suit had been brought in a federal court.

Diversity of citizenship jurisdiction was conferred in order to prevent apprehended discrimination in state courts against those not citizens of the State. Swift v. Tyson introduced grave discrimination by non-citizens against citizens. It made rights enjoyed under the unwritten ‘general law’ vary according to whether enforcement was sought in the state or in the federal court; and the privilege of selecting the court in which the right should be determined was conferred upon the non-citizen. Thus, the doctrine rendered impossible equal protection of the law.”

The decision was also in part a reaction to the practice of “forum-shopping” which had grown up in response to the rule of Swift v. Tyson. That the York test was an attempt to effectuate these policies is demonstrated by the fact that the opinion framed the inquiry in terms of “substantial” variations between state and federal litigation. Not only are nonsubstantial, or trivial, variations not likely to raise the sort of equal protection problems which troubled the Court in Erie; they are also unlikely to influence the choice of a forum. The “outcome-determination” test therefore cannot be read without reference to the twin aims of the Erie rule: discouragement of forum-shopping and avoidance of inequitable administration of the laws.

The difference between the conclusion that the Massachusetts rule is

applicable, and the conclusion that it is not, is of course at this

point “outcome-determinative” in the sense that if we hold the state

rule to apply, respondent prevails, whereas if we hold that Rule 4(d)(1)

governs, the litigation will continue. But in this sense every

procedural variation is “outcome-determinative.” For example, having

brought suit in a federal court, a plaintiff cannot then insist on the

right to file subsequent pleadings in accord with the time limits

applicable in the state courts, even though enforcement of the federal

timetable will, if he continues to insist that he must meet only the

state time limit, result in determination of the controversy against

him. So it is here. Though choice of the federal or state rule will at

this point have a marked effect upon the outcome of the litigation, the

difference between the two rules would be of scant, if any, relevance to

the choice of a forum. Petitioner, in choosing her forum, was not

presented with a situation where application of the state rule would

wholly bar recovery; rather, adherence to the state rule would have

resulted only in altering the way in which process was served.(n.11 in opinion) We cannot seriously entertain the

thought that one suing an estate would be led to choose the federal

court because of a belief that adherence to Rule 4(d)(1) is less likely

to give the executor actual notice than § 9, and therefore more likely

to produce a default judgment. Rule 4(d)(1) is well designed to give

actual notice, as it did in this case.

Moreover, it is difficult to argue that permitting

service of defendant’s wife to take the place of in-hand service of

defendant himself alters the mode of enforcement of state-created rights

in a fashion sufficiently “substantial” to raise the sort of equal

protection problems to which the Erie opinion alluded.

There is, however, a more fundamental flaw in respondent’s syllogism: the incorrect assumption that the rule of Erie R. Co. v. Tompkins constitutes the appropriate test of the validity and therefore the applicability of a Federal Rule of Civil Procedure. The Erie rule has never been invoked to void a Federal Rule. It is true that there have been cases where this Court has held applicable a state rule in the face of an argument that the situation was governed by one of the Federal Rules. But the holding of each such case was not that Erie commanded displacement of a Federal Rule by an inconsistent state rule, but rather that the scope of the Federal Rule was not as broad as the losing party urged, and therefore, there being no Federal Rule which covered the point in dispute, Erie commanded the enforcement of state law.

Respondent contends, in the first place, that the charge was correct because of the fact that Rule 8(c) of the Rules of Civil Procedure makes contributory negligence an affirmative defense. We do not agree. Rule 8(c) covers only the manner of pleading. The question of the burden of establishing contributory negligence is a question of local law which federal courts in diversity of citizenship cases must apply.

(Here, of course, the clash is unavoidable; Rule 4(d)(1) says—implicitly, but with unmistakable clarity—that in-hand service is not required in federal courts.) At the same time, in cases adjudicating the validity of Federal Rules, we have not applied the York rule or other refinements of Erie, but have to this day continued to decide questions concerning the scope of the Enabling Act and the constitutionality of specific Federal Rules in light of the distinction set forth in Sibbach.

Nor has the development of two separate lines of cases been inadvertent. The line between “substance” and “procedure” shifts as the legal context changes. “Each implies different variables depending upon the particular problem for which it is used.” Guaranty Trust Co. v. York, supra, at 108. It is true that both the Enabling Act and the Erie rule say, roughly, that federal courts are to apply state “substantive” law and federal “procedural” law, but from that it need not follow that the tests are identical. For they were designed to control very different sorts of decisions. When a situation is covered by one of the Federal Rules, the question facing the court is a far cry from the typical, relatively unguided Erie choice: the court has been instructed to apply the Federal Rule, and can refuse to do so only if the Advisory Committee, this Court, and Congress erred in their prima facie judgment that the Rule in question transgresses neither the terms of the Enabling Act nor constitutional restrictions.

We are reminded by the Erie opinion that neither Congress nor the federal courts can, under the guise of formulating rules of decision for federal courts, fashion rules which are not supported by a grant of federal authority contained in Article I or some other section of the Constitution; in such areas state law must govern because there can be no other law. But the opinion in Erie, which involved no Federal Rule and dealt with a question which was “substantive” in every traditional sense (whether the railroad owed a duty of care to Tompkins as a trespasser or a licensee), surely neither said nor implied that measures like Rule 4(d)(1) are unconstitutional. For the constitutional provision for a federal court system (augmented by the Necessary and Proper Clause) carries with it congressional power to make rules governing the practice and pleading in those courts, which in turn includes a power to regulate matters which, though falling within the uncertain area between substance and procedure, are rationally capable of classification as either. Neither York nor the cases following it ever suggested that the rule there laid down for coping with situations where no Federal Rule applies is coextensive with the limitation on Congress to which Erie had adverted. Although this Court has never before been confronted with a case where the applicable Federal Rule is in direct collision with the law of the relevant State, courts of appeals faced with such clashes have rightly discerned the implications of our decisions.